The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

A powerful and brave YA novel about what prejudice looks like in the 21st century. Sixteen-year-old Starr lives in two worlds: the poor neighbourhood where she was born and raised and her posh high school in the suburbs. The uneasy balance between them is shattered when Starr is the only witness to the fatal shooting of her unarmed best friend, Khalil, by a police officer. Now what Starr says could destroy her community. It could also get her killed. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, this is a powerful and gripping YA novel about one girl’s struggle for justice.

~~~~~

Some books, I’m not sure I’m the right person to review. Some books are written from so far outside my experience, I don’t know if it’s my place to speak on them, or whether I should just boost the voices of others. This is one of those books; The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas, speaks to a black, female, poor, American experience I just cannot claim to have anything similar to. But it needs to be talked about, because this is one of the most important YA books to come out this year, if not the most important.

The Hate U Give is, as above, a novel about the Black Lives Matter movement, without ever explicitly being about the Black Lives Matter movement in the text, or about any specific police shooting of an unarmed black teenager. Instead, it takes a fictional scenario, and plays it out – from the point of view of the only witness to the shooting, Starr. The whole thing is set up within the first couple of chapters; very rapidly, Thomas drops us into Starr’s world, the two parts she works to keep separate (Garden Heights, the poor, black neighbourhood she lives in) and Williamson (the majority-white private school she attends), the personal and political conflicts raging around her, and the struggles of her life. Those are both ordinary adolescent struggles – boys, friendship groups, school – and larger ones: gang struggles, police racism, complicated family politics.

The Hate U Give ties these all together through the person of Starr; what could be a messy novel with too many threads not really tying together works well in Thomas’ hands as she controls each and every one carefully, bringing them to the fore and pushing them into the background in turn and bringing them together in parallel or running right into each other with a very well controlled hand. At times it doesn’t work quite so well – there are a few rocky patches where transitions between Starr’s self-presentation are hammered home a little too hard, and a few plotlines are just dropped into oblivion without ever going anywhere. There are also moments when it grinds screeching to a halt for Thomas to talk to the reader; while these sections convey important information, they feel clunky and unnatural, as Starr recites information she knows without it really adding anything to the book beyond educating the reader.

The biggest strength of The Hate U Give, though, is also its biggest weakness; the characters. Starr herself, as noted above, is brilliantly written in the centre of all kinds of complicated knots and relationships, and working her way through them is what the book is about; but that requires the other characters be well drawn too. Certainly her family members, especially her Daddy, her Momma, and her Uncle Carlos are all brilliantly drawn, complicated and interesting people, with individual mannerisms, understandings of blackness, and approaches to life, all smart and well-written; but some of the other characters fall flat. The flattest of all is Ms. Ofrah, the community organiser and activist who helps Starr; she is two-dimensional and uninteresting as a character in her own right, serving only to further the plot. Both Chris and Hailey suffer from this too, although that’s not unexpected; Chris, Starr’s boyfriend, is essentially “white ally learning how to be a better ally”, while Hailey is a portrait of white privilege; there’s no reason either needs to be more than that, really. However, that DeVante isn’t very rounded out is disappointing; his role in the book could have been rather more interesting and shown some interesting ideas and parallels, but he’s much more a case study than really allows for that.

It’s also worth noting how strongly this book is connected to generations of African-American culture. The Hate U Give takes its title from a Tupac line, and there’s an implicit struggle in Starr’s parents’ generation over modelling one’s activism on Malcolm X and Huey Newton or Martin Luther King Jr; “Black Jesus” is a constant in life, in houses and art; the soundtrack of the novel is generations of African-American music, from Tupac and NWA to Kendrick Lamar and Ice Cube, with the occasional dips into white superstars of the moment like Taylor Swift. This really does set the atmosphere and tone of the book powerfully.

The Hate U Give can be a tad preachy, with Thomas at times talking at the reader rather than telling the story, and it can at times fall a little flat, but overall, this is a powerful, brutal condemnation of the racist status quo in America, powerfully, brilliantly told from the point of view of one girl.

DECLARATION: This review based on an ARC received from Walker Books, the UK publisher, on request.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

Binti: Home by Nnedi Okorafor

It’s been a year since Binti and Okwu enrolled at Oomza University. A year since Binti was declared a hero for uniting two warring planets. A year since she found friendship in the unlikeliest of places.

And now she must return home to her people, with her friend Okwu by her side, to face her family and face her elders.

But Okwu will be the first of his race to set foot on Earth in over a hundred years, and the first ever to come in peace.

After generations of conflict can human and Meduse ever learn to truly live in harmony?

~~~~~

I loved Binti when it came out in 2015, and have been excited about Okorafor writing sequel-novellas in the series for Tor.com since they were announced in April last year; so getting my hands on a copy when it came out earlier this year was rather exciting. But, with awards and anticipation behind Binti, did the sequel match the opening?

This review will contain SPOILERS for Binti.

Certainly, the novella picks up powerfully where Binti left off; it sees Binti studying at Oozma Uni, dealing with learning about her abilities as a master harmoniser and with the fallout of the events of the last novella – Okorafor writes about Binti’s PTSD and her therapy powerfully, and her emotions are one of the strongest draws of the story; they are really effectively put across to make the volume move the heart as well as the head, and to grip the reader and make them empathise with alien (yet familiar) experiences. The continuing character development is also powerful; Binti’s personal relationship with the world around her, with her family, with Okwu and the Meduse are all central to the plot, and the way Okorafor draws them each out is incredibly powerful and well written.

The plot is less strong, because it isn’t whole. Binti stood alone, and indeed every work of Okorafor’s I’ve read so far has been written as a stand-alone; seeing her approach to writing a series, it seems this is an important point, because Binti: Home takes us part-way through a plot and just ends, on a cliffhanger, having resolved nothing. This isn’t a neatly wrapped ending, it’s the end of the first part of a novel, the first act; the set up is here, but the rest of the story is apparently waiting for the third novella in the trilogy, a definite weakness (why not package the two as one novel?). Okorafor is usually good at endings, so it seems that the problem is in writing semi-endings; things for a book to end on that don’t wrap everything up.

One of the strengths of Binti is also doubled down on in Binti: Home and it’s one alluded to above; namely, that Okorafor is writing, in her (literally) alien experiences, allegories to very real situations and experiences. A lot of Binti and Binti: Home are concerned with prejudice and racism, and how that is taught to us and internalised even against the evidence of our own experience when it is what society believes; so Binti is both the subject of, and unconcious holder of, racist views about others, and Okorafor doesn’t suggest she’s inherently a bad person for this, but would only be if she clung to it in the face of contrary evidence. It’s an very sympathetic portrait of someone who has been raised as racist and cannot simply, in one go, shrug it off; almost too sympathetic perhaps given the real world we live in, but important all the same. However, at another point, Okorafor makes it clear she is not writing allegory; the very brief appearance of Haifa, a trans woman who is matter-of-factly introduced and totally accepted as female, setting the trans experience clearly outside the intentional allegories of the novella. (It is worth noting that while broadly well executed, Haifa’s self-description uses a phrase increasingly criticised and problematised by the trans community).

In the end, Binti: Home doubles down on many of the strengths of Binti, but the lack of any kind of ending makes it not work as a standalone very well; I’m eager for the concluding volume, but wish this had been stronger.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

Battle Hill Bolero by Daniel José Older

Trouble is brewing between the Council of the Dead and the ghostly, half-dead, spiritual, and supernatural community they claim to represent. One too many shady deals have gone down in New York City’s streets, and those caught in the crossfire have had enough. It’s time for the Council to be brought down—this time for good.

Carlos Delacruz is used to being caught in the middle of things: both as an inbetweener, trapped somewhere between life and death, and as a double agent for the Council. But as his friends begin preparing for an unnatural war against the ghouls in charge, he realizes that more is on the line than ever before—not only for the people he cares about, but for every single soul in Brooklyn, alive or otherwise…

~~~~~

It’s no secret that I really enjoyed Half-Resurrection Blues back when I read it in 2015; Daniel José Older’s novels between then and now, Shadowshaper and (in the Bone Street Rumba series) Midnight Taxi Tango, showed a writer stepping up his game each time, so cracking the spine on Battle Hill Bolero, I went in with high expectations.

Taking high expectations to a Daniel José Older novel is a fool’s game, though, because they’re never the right expectations. Urban fantasy is a broad genre, and although the Bone Street Rumba fits perfectly into it, every novel has a very different feel; where the first was a detective novel, and the second more a crime and horror novel, this third is a war story, straight and simple. Only, as with all Older’s writing, it isn’t that simple. Battle Hill Bolero draws the threads of the previous two books together beautifully, with a real ensemble cast; it’s a testament to Older’s skill that the different voices are all still incredibly distinct, with not just attitudes but linguistic ticks all their own, even as they blend those linguistic ticks as they grow together (a really subtle touch). Character development for our pre-existing cast isn’t a huge feature of this novel, although Carlos and Sasha both come to terms with the events that lie between them; but for Krys, our new viewpoint character, we really see some development through the parts of the novel we get, well handled and beautifully written.

I also want to give Older a shout out for including multiple queer characters. Not only bisexual and homosexual characters, but also trans ones – in the background to the novel is Wendy, a nonbinary kid, and one of the secondary characters is a ghost called Redd, a trans man who was alive in the 18th century; the character in Battle Hill Bolero who questions it is a modern kid who gets shut down fast, and everyone else just accepts Redd, and it isn’t brought up again, and that’s a far-too-rare thing, especially in urban fantasy. This is a book in which the only white characters are on the wrong side, and all the queer ones are on the right side, and the trans man survives, and that warms my heart so much.

The only thing that remains to talk about is the plot, which is perhaps where Battle Hill Bolero isn’t strongest, but is by no means weak. The whole novel builds from its opening to its climax inexorably, with a kind of building fury preceding the storm that Older constantly harnesses in all the side-threads; there are a few elements that aren’t as well worked in, including the personal lives of some of our principals, but the whole thing ties into the central conflict that the series, and novel, build towards beautifully. Older continues to handle his action scenes fantastically and with a real viscerality, getting us up close and person and really letting the physicality move us, and his emotional scenes have a similar kind of strength, helping the slightly less smooth parts of the plot get past their bumps easily.

Battle Hill Bolero, then, is a fantastic, brilliantly written capstone to one of the best urban fantasy series of the 21st century, and one of the most aware of what that century looks like: not straight, white, or male, but more like Daniel José Older’s queer, colourful New York.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

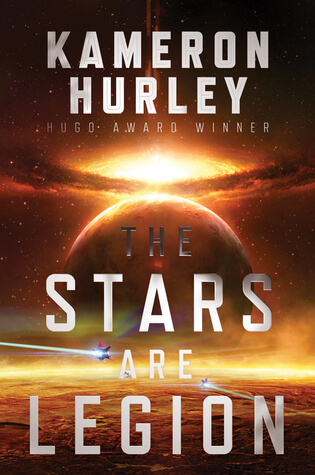

The Stars are Legion by Kameron Hurley

Somewhere on the outer rim of the universe, a mass of decaying world-ships known as the Legion is traveling in the seams between the stars. For generations, a war for control of the Legion has been waged, with no clear resolution. As worlds continue to die, a desperate plan is put into motion.

Zan wakes with no memory, prisoner of a people who say they are her family. She is told she is their salvation – the only person capable of boarding the Mokshi, a world-ship with the power to leave the Legion. But Zan’s new family is not the only one desperate to gain control of the prized ship. Zan must choose sides in a genocidal campaign that will take her from the edges of the Legion’s gravity well to the very belly of the world. Zan will soon learn that she carries the seeds of the Legion’s destruction – and its possible salvation.

~~~~~

I’m a big fan of Kameron Hurley’s Bel Dame Apocrypha and enjoyed Mirror Empire, so when I heard that she had written a new, stand-alone piece of feminist science fiction, I was inevitably very ready to jump on board; thanks to the kind generosity of Penny Reeve at Angry Robot Books, I got to do that a little earlier than most of you…

The Stars Are Legion is in many ways the archetypical Kameron Hurley novel; angrily and unapologetically feminist, grimdark and brutal, and with some very odd biopunk things going on in the worldbuilding. We go in expecting those now, though, so their presence per se is almost not worth commenting on; instead, their specific manifestations are relevant.

The novel as a whole is quite a fast-paced read, powering through a lot of plot very quickly; at times this makes it very choppy, as time is disjointed and unclear (if this was intentional, it isn’t clear that was the case, rather than something approaching carelessness), and at times it founders on repetition of things that were covered earlier being driven home, especially if those things are relevant to the thematic underpinnings. That’s something of a habit for Hurley; this is less choppy in many ways than previous novels, and has a much better approach to concealed information, with Zan’s lost memory and the way Jayn, our other viewpoint character, talks about things feeling naturally avoidant rather than forced for plot reasons. The eventual resolution feels forced though, and doesn’t really fit with the tone of the rest of the novel; whether Hurley or her editors wanted it, The Stars Are Legion wraps up in a way that grinds harshly against what came before.

In terms of character, though, the tight focus of The Stars Are Legion means it’s one of Hurley’s most accomplished books so far. Having only Zan and Jayn as viewpoint characters means we really get into their heads very deeply, and having quite a small ancillary cast to those protagonists allows Hurley to paint them vividly through both interactions with the principals and with each other; across the novel we see a variety of different expressions of personhood accompanied by different responses to the weird world Hurley has constructed. It’s an impressive feat to achieve that kind of variety, and to draw out the characters so powerfully and individually; although Zan’s characterisation seems to falter at the end and her decisions come out of left field, rather than reading as a natural extension of her development up until that moment.

This is a dark novel; The Stars Are Legion, as mentioned above, is hardly out of line with the place in the grimdark movement that Hurley has carved for herself. The worldbuilding is incredibly biopunk-centred, and that means that not only do the sections involving violence towards other people have viscera and gore, but much of the travel does; this is also a book in which we see multiple births, although those are almost sanitised compared to much of the rest of the viscera Hurley provides. It’s an interesting contrast, then, to look at the birthing scenes in contrast with, say, violence done against other people; there’s much more focus on bodily fluids in the latter, much more on noises in the former.

The Stars Are Legion is an all-female novel, set in an all-female world; that leads Hurley to make some decisions which are… arguably problematic, especially for trans people. For a start, no trans people exist in this world; every human is a cis female born with a working womb, for reasons that become clear as the novel progresses, but they still all identify as women, as if there’s some other thing they’re identifying against, despite that clearly not being the case. Furthermore, in this world shorn of trans people, a sincere and deep wish of many trans women, for working womb transplants, is not only possible, but something that happens on multiple occasions; it’s not regular, but it’s clearly doable, which feels a little painful to this queer. However, the feminism of the novel is otherwise very strong, with the cast being clearly marked as not white (and whiteness being noted as an exceptional state in one character) and the approach to culture being to create it virtually wholesale.

In the end, then, while The Stars Are Legion isn’t a perfect novel on either aesthetic or political grounds, I think it is probably Hurley’s best work yet, and a brilliant piece of feminist science fiction.

DISCLAIMER: I am friends with Kameron Hurley and support her writing on Patreon. She has previously contributed two guest posts to this blog. I am also friends with Penny Reeve, publicist at Angry Robot Books, UK publishers of The Stars Are Legion. This review is based on a finished copy sent to me by the publisher.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

Octavia Butler’s Kindred, adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings

More than 35 years after its release, Kindred continues to draw in new readers with its deep exploration of the violence and loss of humanity caused by slavery in the United States, and its complex and lasting impact on the present day. Adapted by celebrated academics and comics artists Damian Duffy and John Jennings, this graphic novel powerfully renders Butler’s mysterious and moving story, which spans racial and gender divides in the antebellum South through the 20th century.

Butler’s most celebrated, critically acclaimed work tells the story of Dana, a young black woman who is suddenly and inexplicably transported from her home in 1970s California to the pre–Civil War South. As she time-travels between worlds, one in which she is a free woman and one where she is part of her own complicated familial history on a southern plantation, she becomes frighteningly entangled in the lives of Rufus, a conflicted white slaveholder and one of Dana’s own ancestors, and the many people who are enslaved by him.

Held up as an essential work in feminist, science-fiction, and fantasy genres, and a cornerstone of the Afrofuturism movement, there are over 500,000 copies of Kindred in print. The intersectionality of race, history, and the treatment of women addressed within the original work remain critical topics in contemporary dialogue, both in the classroom and in the public sphere.

Frightening, compelling, and richly imagined, Kindred offers an unflinching look at our complicated social history, transformed by the graphic novel format into a visually stunning work for a new generation of readers.

~~~~~

Earlier this week, I posted my review of Octavia Butler’s seminal 1979 novel Kindred; this is a slightly odd review because rather than talking about the work itself, I’m going to be talking about it in relation to the work of which it is an adaptation, and therefore that earlier review is a necessary read before going further.

Adapting a novel into a more visual format can be achieved in a number of ways – we’ve all seen films adapting novels: dropping subplots, complexities, changing how characters looked, or simply taking a core simple idea and mangling everything else beyond recognition (Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, anyone?). Graphic novel adaptations of novels seem to fare on average better, perhaps because they have a similar length in many cases, and because they can handle non-dialogue language better; from the Manga Shakespeare series to this volume, there are a variety of approaches. Kindred takes a very direct, literal approach: almost all the words (with one clear exception) are taken directly and exactly from the novel as quotes, with occasional reordering – both narration in caption boxes, and dialogue, directly as speech. Because of the way Butler wrote, this can at times be a little odd – there’s a particular moment when Dana talks about being at a whipping being impossible to imagine just from seeing images of one, and these thoughts are captions to pictures of one, for instance. There are also occasions on which events are slightly reordered – there doesn’t seem to ever be a clear reason for the slight changes, apart from cutting a few panels out here and there by combining things, so presumably it was a space consideration, a reasonable concern given that nothing was lost.

The aforementioned clear exception is an odd one, though; it concerns one of the moments when Butler may, or may not, have been being rather subtly pointed in Kindred. A (presumably black) friend of Dana’s gives her and Kevin a blender as a wedding present in the novel; this is, perhaps, a commentary on the mixed race marriage, on the idea of “blending” races. In the adaptation, though, Duffy and Jones replace the blender with steak knives – arguably a possible foreshadowing/hindshadowing of other events, given when it’s revealed, but it seems a very strange choice of alteration when so much of the rest of the text is unchanged at all from Butler’s own words.

A graphic novel is more than just words, though, of course; it is also the art. Kindred has an art style that is often seen in the more artsy of the independent comics out there, reminiscent of Jeff Stokely’s art on The Spire. It’s not quite naturalistic without being either symbolic rather than literal or the shiny-happy people of Marvel’s house style; it’s a little rough looking, a little off normal, and I found that a little frustrating, because it never quite fitted the approach the text takes, which is totally matter of fact. There were some fantastic grace notes (near the start of the book, Dana is shelving her books after moving house, and drops some – one of which is Patternmaster, Butler’s debut novel), but overall, the art is more distancing, and reductive, than helpful.

In the end, Kindred is an amazingly powerful novel; this adaptation doesn’t quite manage to capture that power, and occasionally seems to have failed to understand how Butler accomplished it. Nnedi Okorafor’s brilliant introduction is a must, though!

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

On her 26th birthday, Dana and her husband are moving into their apartment when she starts to feel dizzy. She falls to her knees, nauseous. Then the world falls away.

She finds herself at the edge of a green wood by a vast river. A child is screaming. Wading into the water, she pulls him to safety, only to find herself face to face with a very old looking rifle, in the hands of the boy’s father. She’s terrified. The next thing she knows she’s back in her apartment, soaking wet. It’s the most terrifying experience of her life … until it happens again.

The longer Dana spends in 19th century Maryland – a very dangerous place for a black woman – the more aware she is that her life might be over before it’s even begun.

~~~~~

I’ve had this classic of African American genre fiction on my shelves for a long time, and was finally prompted to read it by the release of a graphic novel which spins off the work – asking Nnedi Okorafor if I should read the book or the comic first, the definitive answer was the book, so I have! (Thursday’s review will be of the comic).

Kindred is one of those books that I, arguably, should not be reviewing, and should just be describing. It’s about experiences essentially foreign to me, not because of fictionality, but because of reality; I am spared much of what happens in the novel not because it is fictional, but because I have privilege – white privilege, often perceived male privilege, and the luck to be born in 1989, not 1789. On the other hand, Butler’s intent in the novel seems to be as much about making immediate and personal the impact of slavery for the modern white reader as anything else, so I might be the perfect reviewer.

On that score, Kindred is brutally brilliant. It drops us, with our 20th century understanding of how the world works (1976, so things have changed even since then), repeatedly back into the world of the antebellum Southern States; Dana, our narrator, has to adjust to the survival strategies of a black slave in 1819, instead of the survival strategies a middle-class black woman married to a white man needs. Butler doesn’t let the brutality go unmarked, talking about the difference between seeing it on film (as, perhaps, in the earlier seminal TV series Roots) and witnessing it in person – the way more senses are drawn in and it becomes more viscerally appalling; she also then goes on to demonstrate the brutality of it directly on the body of Dana herself. Kindred doesn’t shy away from the parts of slavery that are often covered up, either; rape by the master, whether violent or otherwise, is an everpresent threat in the novel, and it isn’t sexy, it’s appropriately horrifying, shocking, and damaging. Nor are the consequences of rape pretended away; that is, the children that resulted from rape are, in fact, an instrumental plot point in the novel, and also something Butler grapples with powerfully in terms of their modern legacy in the United States of America.

Linked to this is Kindred‘s empathetic approach to the psychology of slavery. Slavery colours every interaction in Kindred, both past and present, changing and altering the power dynamics, the human dynamics, the boundaries of behaviour, the approach of one person to another; it changes people’s motivations in ways small and large, and what they have to consider in terms of consequences to their actions. Butler really lays out the way white slave owners dehumanised and stripped the agency from all black people, slave or free, while slaves had to consider the cost of every action weighed against the punishment and consequences for themselves and everyone around them. It’s conveyed subtly and more strongly as Dana spends more time in the past, and as the mentality of a slave increasingly changes her thinking about the world she is in; Butler builds it up subtly, only at the end having Dana really explicitly talk about it but making it an undercurrent running throughout Kindred.

The other thing Kindred powerfully grapples with is modern gulfs in understanding; this is a time travel novel with a black protagonist, after all. Kindred delves into what that means with Dana and Kevin, her white husband, having fundamentally different experiences of and understandings of the past; their present experiences are similar, but their experiences in the 19th century underline just how much racism still persists in the modern day, by drawing out the point. Butler never hammers the point home in a blunt conversation, but just throughout the novel allows the theme to emerge of how different the experiences in history of black and white people were; it’s a powerfully effective approach.

Kindred isn’t the only book about slavery out there; but it’s one of the most effective I have ever read at getting across the psychology of both slave and master in a slaver society, and Butler’s novel should keep being read, if not be made required reading.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

Roller Girl by Vanessa North

Recently divorced Tina Durham is trying to be self-sufficient, but her personal-training career is floundering, her closest friends are swept up in new relationships, and her washing machine has just flooded her kitchen. It’s enough to make a girl cry.

Instead, she calls a plumbing service, and Joanne “Joe Mama” Delario comes to the rescue. Joe is sweet, funny, and good at fixing things. She also sees something special in Tina and invites her to try out for the roller derby team she coaches.

Derby offers Tina an outlet for her frustrations, a chance to excel, and the female friendships she’s never had before. And as Tina starts to thrive at derby, the tension between her and Joe cranks up. Despite their player/coach relationship, they give in to their mutual attraction. Sex in secret is hot, but Tina can’t help but want more.

With work still on the rocks and her relationship in the closet, Tina is forced to reevaluate her life. Can she be content with a secret lover? Or with being dependent on someone else again? It’s time for Tina to tackle her fears, both on and off the track.

~~~~~

Sports novels (or, indeed, sports generally) and romance novels aren’t things I’m usually interested in – indeed, sports usually gets me to tune out completely, I care that little about it. So a romance novel centred on a sport, even one I find interesting, like roller derby? That’s going to be a tough sell; but I was recommended Roller Girl for its queerness and, well, took a punt…

It turns out what my life might have been missing was queer sports romance books, because this was something of a balm to my soul. Centred on trans woman Tina, who is relatively recently divorced in the wake of her transition, Roller Girl shows a supportive queer community in the traditionally queerphobic space of sports; it talks about transness and queerness frankly, but also kindly; it shows spaces of female friendship and solidarity that are open and welcoming to queer and trans women. Indeed, by the novel’s end, North has built on that to show enby openness too; this is queer-positive, sex-positive, kink-friendly, and simply achieves all that, without trying (too much; occasionally it can be a little Queer 101, although textually justified as being 101 for a straight character).

Tina is an absolutely brilliant character, who will resonate with a lot of people; she’s unsure of herself, constantly self-questioning, and never realising her own positive worth and impact on people around her. Indeed, Roller Girl can be read as a novel about (dysphoria-linked) depression as much as anything else, and how Tina comes into herself through both supporting and being supported by others; and it’s a book about coming out of the closets, as a process rather than a single moment, and the impact an ordinary person coming out of the closet can have on people. As a character study it’s small-scale but every individual really jumps off the page, from romantic partner Joe, to teammate Stella, from old friend and wakeboard rival Ben to Jeffrey, a personal training client; Vanessa North uses very economical methods to give them characters, but none are simple and two-dimensional, they’re complex and interesting characters with obvious stories in their own rights (some literally).

The place where it perhaps falls down is on plot. Roller Girl forgets certain things, like time – there appear to be giant emotional jumps and time jumps not signalled on the page at times, and everything either takes place in the space of two months or a week or some undetermined time, there are far too few markers – and there isn’t really time to build up some of the things North needs to earn her moments of emotional catharsis, so it can feel a little forced at times; the conclusion especially feels wholly unearned, as if we’re missing a good chunk of story that North just wasn’t interested in writing. The character development somehow avoids feeling rushed by this, but the development of relationships at times can very much feel forced by narrative necessity.

One final note about Roller Girl, and that is that it is hot. There are only a couple of sex scenes, but each one is written with an intensity and force, and an understanding of personal kinks and drives, of individual needs and desires, and of mutual consent, that steams off the page; North acknowledges the awkward fumbling, the passionate drive, and the ridiculous joyousness of (good) sex and writes it into her book, avoiding cliche and passionless description alike in some really brilliant scenes that jump out from the page.

Roller Girl might not be perfect, but it’s the book I needed the day I read it, and Vanessa North has written something that works as a balm for this troubled queer soul.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

Can I Tell You About Gender Diversity? by C. J. Atkinson, illus. Olly Pike

Meet Kit – a 12 year old undergoing medical transition – as he talks about gender and the different ways it can be explored. He explains what it is like to transition and how his friends, family and teachers can help through talking, listening and being proactive.

With illustrations throughout, this is an ideal way to start conversations about gender diversity in the classroom or at home and suitable for those working in professional services and settings. The book also includes a useful list of recommended reading, organisations and websites for further information and support.

~~~~~

Can I Tell You About Gender Diversity? first came to my attention thanks to its media coverage in the wake of condemnation by such luminaries as Norman Tebbit, former Thatcherite Cabinet member and rabid queerphobe, and Sarah Vine, columnist for the vile rag the Daily Mail. It is a resource for (young) children and for adults who work with them to better understand gender diversity, and part of a series of such volumes on different issues from the same publisher.

The book is divided into two parts: first, forty-odd pages, with illustrations, about Kit, a fictional trans boy who tells us about growing up so far, accessing the Gender Identity Clinic, accessing school facilities, resources and support, going onto hormone blockers, and his trans friends, who include nonbinary people and a trans girl. This section of Can I Tell You About Gender Diversity? is clearly aimed at children, both those who are trans and those who are cis, as a broad explanation of trans issues; it uses simpler language, although it introduces things like neopronouns and legal issues around the Equality Act (2010). It also presents, very clearly, things like the difference between gender identity, gendered stereotypes, sex, and sexuality, and explains how those are unrelated, a key thing for children.

The second section of Can I Tell You About Gender Diversity? is about half the length and focuses heavily on explaining to adults how they can support trans children, at home, at school and in other settings. This section gets more technical and specific, but also brushes lightly over a number of issues; one of the major problems is its UK-centric nature (GICs, GIRES, and the Equality Act (2010) are all UK institutions), given that it is for distribution internationally, and another is its occasional inaccuracies. Atkinson’s guidance about the law, for instance, suggests that the Equality Act (2010), in protecting gender reassignment, protects people whether or not they medically transition; in reality, however, the position is that only those who intend to, are, or have undergone medical transition are protected (therefore, for instance, I am not), an important mistake. However, the clarity of explanation of the duties of confidentiality and support are welcome.

The one other area Atkinson glosses over rapidly in Can I Tell You About Gender Diversity? is that of intersex people. There is one brief mention of intersex people, and there is an entry in the glossary, but some more information, especially for parents and professionals, might have been helpful; after all, intersex children are more likely than most to have medical procedures forced upon them by adults who do not understand intersex conditions, and to be raised in ways that very strictly enforce gender conformity. A little more attention paid to these issues would have been welcome.

In the end, though, I wish something like Can I Tell You About Gender Diversity? had been in circulation when I was at school; something that might have put a name to some of the unease I felt about myself, and helped me understand it. C. J. Atkinson has produced a vitally important resource I hope schools across the UK capitalise on.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

A groundbreaking work of science fiction, The Left Hand of Darkness tells the story of a lone human emissary’s mission to Winter, an unknown alien world whose inhabitants can choose—and change—their gender. His goal is to facilitate Winter’s inclusion in a growing intergalactic civilization. But to do so he must bridge the gulf between his own views and those of the completely dissimilar culture that he encounters. Exploring questions of psychology, society, and human emotion in an alien world, The Left Hand of Darkness stands as a landmark achievement in the annals of science fiction.

~~~~~

Some books age well, relatively timeless in their concerns, approach, and writing. Some age poorly, speaking only to a very specific time and place. Most books age somewhere in between, aspects dating badly but others still having a resonance. The Left Hand of Darkness is often considered to be one of the first kind; but on this reread, I wanted to see if that really was the case.

The fact is plainly that it is not. In the introduction, Le Guin explicitly describes The Left Hand of Darkness not as a prediction of where humanity will in future go, but as a reflection of gender and society at the time it was written; given that it was written in 1969, and both our understanding of gender and of society have changed a lot in the intervening four and a half decades, that it has dated isn’t a surprise. But some of the ways in which it has dated are significant, given that (unlike, say, Joanna Russ’ The Female Man) it is still very widely praised for its portrayal of a nonbinary approach to genders. Part of the problem is that the narrator of most of the book is trapped in a very 1960s approach to gender; a very binarist model, with masculine/male superior and feminine/female inferior; public/domestic, forceful/submissive, strong/weak, violent/peaceful, straightforward/dissembling are all read through a male/female binary that reads as singularly outdated to the modern reader. Even those parts of the book narrated by a Gethen native, an “hermaphroditic neuter” as Le Guin describes them, is affected by these things.

A further problem is that these “hermaphroditic neuters” (who enter kemmer, or heat, about four days in twenty-six and only have a dominant binary sex then) are referred to, consistently, as “he”, “him”, “man”, etc; they are gendered, both by Genly Ai and by Estraven, our native narrator, who surely ought to have to hand a gender-neutral pronoun, whether neo or otherwise. As it is, the times they enter kemmer as female become slightly strange, as if there is far more change; this is inconsistent with the actual words on the page, but the implication of the defaulting all characters to male by all the narratorial voices.

The biggest problem from a queer point of view, though, is that queerness is completely erased from The Left Hand of Darkness. Homosexuality is implied as a strange minority act in the Ekumen, and nonexistent on Gethen, the setting of The Left Hand of Darkness, as if given the choice everyone would have heterosexual pairings; sex arises from oppositional sex to the person one is pairing with in kemmer, hence all sexual pairings are heterosexual, even though people are clearly referred to as having preferred sexual characteristics in kemmer. Furthermore, Genly Ai has no experience with anything but an incredibly simple from-birth binary; the only breach of that binary is on Gethen, meaning trans people, nonbinary people, third gender people, agender people, intersex people, etc? None of these people exist in the world of the Ekumen; Le Guin addresses the questions of sex and gender as utterly inseparable except by a subspecies of humanity, and The Left Hand of Darkness makes, of anyone outside the simple binary, an Othered alien. We are not, in the world of The Left Hand of Darkness, people; we are Other, fundamentally alien, fundamentally estranged from humanity, and indeed fundamentally lesser because of it. This is, from that point of view, an incredibly uncomfortable book to read.

As far as a broader review goes, the book has suffered less from the ravages of time. The Left Hand of Darkness includes a look at a something-like-Soviet Communist state and a semi-feudal, semi-anarchist collective state, noting the shortcoming and drawbacks of each; it features a fantastic amount of both politicking and what might be referred to as fantasy-mountaineering, brilliantly balanced with a consistency of characterisation that really works well; and a philosophical strain, drawing on various non-Western philosophies, that requires real engagement with. Indeed, it’s the balance of these elements that works best, but is fundamentally a minority of the book; the mountaineering section is fantastically evocative and by turns claustrophobic and agoraphobic, but still essentially concerned with the questions of gender noted above, which the book is ill-prepared to deal with. The best writing in the book is environmental, evoking the cold, stark beauty of an ice sheet or the strange mixture of slush and ash around a frozen volcano; Le Guin excels at these descriptions, undoubtedly.

The Left Hand of Darkness, then, is a book that challenged views of gender in 1970, undoubtedly, although even then not so radically as one might imagine; in 2016, it is hopelessly dated, and even, for those of us for whom the binary is a poor, uncomfortable, damaging fit, actively destructive.

This review is dedicated to Corey Alexander, who was asking for more reviews of The Left Hand of Darkness by trans and enby reviewers!

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write these reviews by contributing to my Patreon.