Home » Posts tagged 'military science fiction'

Tag Archives: military science fiction

The Red: First Light by Linda Nagata

There Needs To Be A War Going On Somewhere

Lieutenant James Shelley commands a high-tech squad of soldiers in a rural district within the African Sahel. They hunt insurgents each night on a harrowing patrol, guided by three simple goals: protect civilians, kill the enemy, and stay alive—because in a for-profit war manufactured by the defense industry there can be no cause worth dying for. To keep his soldiers safe, Shelley uses every high-tech asset available to him—but his best weapon is a flawless sense of imminent danger…as if God is with him, whispering warnings in his ear. (Hazard Notice: contains military grade profanity.)

~~~~~

The Red: First Light is military science fiction that sits somewhere between post-9/11 and post-Eisenhower antiwar politics; clear as to who to target – the Military-Industrial Complex, here described as defence contractors or DCs – but mistaking the reality of modern war, wherein contractors increasingly do the work on the ground, not the government-run military forces. Not that Nagata doesn’t acknowledge private security forces and independent military contractors, who are given a significant role in especially the non-“formal war” conflicts in the novel, but that they are sidelined away from things like anti-insurgency operations, something anyone familiar with the way we are currently at war in the Middle East will recognise as strange. It’s also a book whose politics are worn on its sleeve; Shelley is very outspoken and blunt in his anti-MIC rants which, while not being simply voice of the author, are clearly rewarded by Nagata.

It doesn’t help that the military itself does not reflect the real world military or the direction in which that is going; The Red: First Light has a military full of middle-class people from middle class backgrounds, on the whole, with good educations and alternative prospects. Unfortunately, this is not what the military of Western nations look like any more, increasingly drawing on the working classes and those with no chance for good education or good jobs, offering employment where otherwise there might be none; this failure to engage with the exploitative nature of the military-industrial complex makes it seem like the problem is only in the way it creates wars in foreign countries, not in the global wealth politics involved, a curious if telling omission.

The Red: First Light is not, however, simply a political manifesto against the financially-required wars or the eternal economic need for conflict. It is also a military science fiction novel in its own right, and this is where Nagata works some real narrative magic. The action inherent to a military science fiction novel can often feel forced, and the suspense unreal, but when our protagonist loses his legs early on it is clear the stakes are actually real, and that risk exists for all the characters; this early establishment of the stakes works very well when Nagata relies on it later on to question how real the stakes are. The action is the standard fast-paced violent material, but with a moral element not always found in milSF; The Red: First Light does deal with the issues of the morality of war and of following orders in battle while also maintaining the tension necessary to this kind of novel.

Character is a weaker area, as again is perhaps common to the genre. Shelley is the rebel who fits into the system, fighting against it while also reliant on it; the rest of the cast are really just ciphers against whose backdrop Shelley acts on the world, and who exist only for their emotional impact on Shelley. Nagata even manages, towards the end of the novel, to fundamentally fridge a character, who serves little narrative purpose before that except to be an emotional tie for Shelley; The Red: First Light really doesn’t ascribe much interest or humanity to any of the rest of its cast, and that has a sadly flattening on its emotional beats. The reality of the novel is that its first-person viewpoint just doesn’t care about other people, and while that could be used interestingly, it results instead in an awful lot of telling us about character rather than showing it – the cast being either indistinguishable or, in the case of a few characters like Ransom, distinct only because of their broad brushstrokes of personality.

The Red: First Light has one other plot element so far not mentioned, and that is the Red itself, the strange unknown force in the electronic Cloud that seems to be keeping Shelley alive. The problem here is again one of patchiness; not so much that its attention comes and goes – which allows for interesting dynamics in the story, including Shelley’s reliance on it and others’ faith in him based on it – but the attention that characters pay to it. Sometimes they are paranoid about its impact, other times blasé about its existence, and sometimes acting and thinking as if it didn’t exist; it feels almost as if Nagata sometimes just could not be bothered to factor it in to her characters’ reactions, and didn’t do a consistency-edit on that at any point.

In the end, The Red: First Light is a very exciting and fastpaced military science fiction novel, but Nagata disappoints on the character front and the attempts to engage with serious real-world issues of politics fall singularly flat.

The Heart of Valour by Tanya Huff

Her latest mission sees newly promoted Gunnery Sergeant Torin Kerr escorting a recuperating major and his doctor to Crucible, the Marine Corps training planet. But when the troops are suddenly attacked by their own drones, Kerr is caught in a desperate fight to protect the major, his doctor and a platoon of untried recruits.

~~~~~

The third of Huff’s Valour books feels, in many ways, like a return to the first, with a little of the paranoia of the second thrown in for good measure. The Heart of Valour once again sees Torin Kerr given a group of soldiers she doesn’t know for a specific mission; in this case it is theoretically the not-so-simple task of escorting a major through his paces as part of his rehabilitative programme on a training run for recruits, which becomes horribly real – and horribly live-fire.

If this conjures up images of Valour’s Choice, in which Kerr is sent on a diplomatic mission which turns into a rerun of Rourke’s Drift, that is a reminiscence actually mentioned in The Heart of Valour; while there is a sort of intrigue subplot trying to peek out from among the action, it’s one whose content is so obvious, and whose resolution so clear from the start, that it is nearly pointless and fails to add much. In fact, that particular subplot simply seems to be a way to have Craig Ryder hanging about, rather than constructive of itself, or perhaps building towards something in the next book; in either case it feels clumsily bolted on and slows down the main, core military science fiction story.

That core of The Heart of Valour is, as noted above, rather similar to the first book in the series, but excellently carried off; the way Huff treats her Marine recruits, the majority of characters in the novel, is sympathetic and interesting, similar to the way she has treated Marines in prior books but also touching on their lack of experience and their heroisation of Marines with actual service. Huff also introduces some interesting new wrinkles, including some backstory to the di’Takyan; this introduces a subplot related to the way integration of different cultures affects unit cohesion and function, and is interestingly addressed, especially in the way discussion continues throughout the book on Marine problems versus species problems.

Mind you, the specific choice of cultural difference is a rather problematic one. The Heart of Valour sees a character taken out of action by the use of illegal hormone treatments to avoid what is essentially a cross between menopause and gender-change; the resolution to this plot is not sympathetic to this character, and avoids touching on discussion of why they might wish to avoid this change, instead presenting it as idiocy to not simply give in and go through with it. As a genderqueer reader, what Huff is doing here strikes very close to trans issues, especially issues of trans service in the emergency services and the army; and her conclusion that attempting to avoid betrayal by one’s own body is a foolish, dangerous decision is one that we see reproduced often enough as it is, and whose counterpoint – that one’s body should reflect one’s self, not vice versa – is far too rarely argued.

Heart of Valour, then, continues the fun, readable and enjoyable adventures of Torin Kerr, but also continues Huff’s track record of some particularly problematic writing in this series…

The Better Part of Valour by Tanya Huff

When Staff Sergeant Torin Kerr makes the mistake of speaking her mind to a superior officer, she finds herself tagged for a special mission for the interplanetary Confederation to act as protector to a scientific exploratory team assigned to investigate an enormous derelict spaceship. Along with her crew and her charges, Kerr soon finds herself in the midst of danger and faced with a mystery that takes all her courage and ingenuity to solve. This sequel to Valor’s Choice, featuring a gutsy, fast-thinking female space-marine protagonist, establishes veteran fantasy author Huff as an accomplished spinner of high-tech military-sf adventure.

~~~~~

Valour’s Choice is one of those military science fiction novels that defies much of the standard understanding of the subgenre, especially the conservatism of it; The Better Part of Valour sees Huff following many of those themes through…

Once again, Kerr is sent on a mission of vital importance with too little information and under a misleading brief from General Morris. Given the way Valour’s Choice ends, this is perhaps a little surprising; that Kerr still has her post as Staff Sergeant after her insubordination is rather unexpected, and that she is the go-to Marine for dangerous missions is, while earned, unexpected. On the other hand, Huff makes it work; her portrayal of the military relations around the different ranks and between them, and between the services at different levels, shows the way she sees the military working with a sense of humour as well as a certain degree of functional disfunctionality.

That, of course, is more subplot than plot; the plot here is one gamers will recommend from any number of space-based science fiction shooters, and that Warhammer 40,000 players will recognise as the standard encounter with the Tyrannids: The Better Part of Valour sees Kerr leading a group of specialist Marines assembled from various regular units into an unidentified alien ship in order to analyse it. Unsurprisingly, what early on seems completely routine rapidly takes a turn for the more violent, but also the quite weird; Huff creates a sense of the strange and uncanny about the story and the ship even while the blunt humour, sexuality, and fast, almost breezy style keep the sense of a military science fiction that just wants to get the job done in place.

As usual, character really makes this; The Better Part of Valour sees Kerr joined by a completely new cast, and it is worth reading for the different characters and interactions we see in this sequel. Huff has great control over her characters, with each having different voices but similar, not across species alone but also across roles – such as the universality of Marine grunts, and the di’Takyan sex obsession. The interests, ideals and thought processes of each character are unique but all are also distinctly human; while slightly strange in that most of these characters are human, it makes this an intensely relatable book.

Once again, we don’t approach the Confederation novels for deep, meaningful meditation on the human condition, but Huff does deliver enjoyable, and interesting, military science fiction with both humour and excellent characters, and The Better Part of Valour builds on the strengths of Valour’s Choice to be a better novel than it.

If You Liked… Then Try…: Ancillary Justice

Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice swept the science fiction awards this year, winning the Arthur C. Clarke, BSFA, Hugo and Nebula Awards among others, an unprecedented feat. It’s also one of my favourite novels, and one I like to share with people as much as possible, for its scope and scale, its approach to gender, its fast-paced writing, and, well, general wonderfulness. But it’s not an isolated example; here are some books you might like if you enjoyed Ancillary Justice:

Tanya Huff’s Valour series of military science fiction have many elements in common with Ancillary Justice, not least the fast-paced writing and the sheer joy in science fiction taken. It goes deeper than that, though; both deal with, on some level, the traumas and crimes of war, the difficult decisions, and the idea of comradeship. Huff doesn’t deal with gender to the same extent as Leckie, certainly not with a full on attack on the standard gender paradigm, but gender stereotypes are out of the window. Furthermore, not only has the Voice of God declared all characters bisexual unless stated otherwise, but they actually are bisexual – that is, we see all sorts of configurations of various sexualities, as well as open relationships, polyamory and more, in a fantastic way. My review of the first book, Valour’s Choice.

Tanya Huff’s Valour series of military science fiction have many elements in common with Ancillary Justice, not least the fast-paced writing and the sheer joy in science fiction taken. It goes deeper than that, though; both deal with, on some level, the traumas and crimes of war, the difficult decisions, and the idea of comradeship. Huff doesn’t deal with gender to the same extent as Leckie, certainly not with a full on attack on the standard gender paradigm, but gender stereotypes are out of the window. Furthermore, not only has the Voice of God declared all characters bisexual unless stated otherwise, but they actually are bisexual – that is, we see all sorts of configurations of various sexualities, as well as open relationships, polyamory and more, in a fantastic way. My review of the first book, Valour’s Choice.

Jacqueline Koyanagi’s Ascension is possibly the most diverse novel I have ever read. Koyanagi’s cast includes chronically ill, trans, non-neurotypical, variously sexually queer characters, many of whom are people of colour and a large proportion of whom are not male (female, genderqueer, etc). This isn’t a matter of comment for Ascension, although some of the more unexpected representations – Otherkin, for instance – are, while normalised, still questioned by the protatonist. Koyanagi’s debut isn’t without its problems, including some very rocky prose and poor plotting, but that’s not to say it’s not worth your time despite this.

Jacqueline Koyanagi’s Ascension is possibly the most diverse novel I have ever read. Koyanagi’s cast includes chronically ill, trans, non-neurotypical, variously sexually queer characters, many of whom are people of colour and a large proportion of whom are not male (female, genderqueer, etc). This isn’t a matter of comment for Ascension, although some of the more unexpected representations – Otherkin, for instance – are, while normalised, still questioned by the protatonist. Koyanagi’s debut isn’t without its problems, including some very rocky prose and poor plotting, but that’s not to say it’s not worth your time despite this.

Melissa Scott’s Shadow Man is one of the most famous works of science fiction to have really questioned the gender binary, and one of the earliest to do it well. The clash of cultures between a five-gendered and a binary-gendered society still has problems related to essentialist assumptions, even while challenging binarist thinking, but it at least opens the discussion up in an interesting way, similar to the questioning of our understanding of gender the Raadch of Ancillary Justice provokes. Like Ancillary Justice and, more so, Ancillary Sword, Scott’s Shadow Man also tackles issues of colonialism and the relationship between dominant and nondominant cultures, and ethical relations between them, in a brilliantly done and never overstated way. My review of Shadow Man.

Melissa Scott’s Shadow Man is one of the most famous works of science fiction to have really questioned the gender binary, and one of the earliest to do it well. The clash of cultures between a five-gendered and a binary-gendered society still has problems related to essentialist assumptions, even while challenging binarist thinking, but it at least opens the discussion up in an interesting way, similar to the questioning of our understanding of gender the Raadch of Ancillary Justice provokes. Like Ancillary Justice and, more so, Ancillary Sword, Scott’s Shadow Man also tackles issues of colonialism and the relationship between dominant and nondominant cultures, and ethical relations between them, in a brilliantly done and never overstated way. My review of Shadow Man.

It’s impossible to talk about Ancillary Justice without also talking about Iain M. Banks and the Culture, despite the lack of direct influence from one on the other. That’s in large part because the Culture and the Raadch have a number of features in common, including the prominence of AIs – treated very similarly by the writers, but very differently in their worlds – and the non-binarist approach to gender. It’s also something deeper, though; both the Culture novels and the Raadch address issues of cultural colonialism and the homogenisation of culture by a dominant force, albeit using different kinds of force. They’re also both extremely good writers, Banks famously so; and the combination of fast, fun romp with very serious issues and a certain degree of tragedy that both achieve is very notable.

It’s impossible to talk about Ancillary Justice without also talking about Iain M. Banks and the Culture, despite the lack of direct influence from one on the other. That’s in large part because the Culture and the Raadch have a number of features in common, including the prominence of AIs – treated very similarly by the writers, but very differently in their worlds – and the non-binarist approach to gender. It’s also something deeper, though; both the Culture novels and the Raadch address issues of cultural colonialism and the homogenisation of culture by a dominant force, albeit using different kinds of force. They’re also both extremely good writers, Banks famously so; and the combination of fast, fun romp with very serious issues and a certain degree of tragedy that both achieve is very notable.

So, those are the four big recommendations I’d make to fans of Ann Leckie and Ancillary Justice… but now it’s time to throw open the comments to the floor! Why am I wrong? What have I missed? What would, or wouldn’t, you recommend?

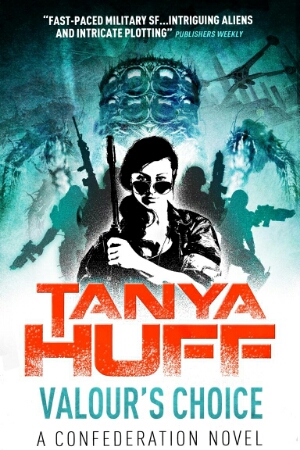

Valour’s Choice by Tanya Huff

In the distant future, two alien collectives vie for survival. When the peaceful Confederation comes under attack from the aggressive Others, humanity is granted membership to the alliance – for a price. They must serve and protect the far more civilized species, fighting battles for those who have long sinces turned away from war.

Staff Sergeant Torin Kerr and her platoon are assigned to accompany a group of Confederation diplomats as they attempt to recruit a newly discovered species as allies. But when her transport ship is shot down, the routine mission becomes anything but, and Kerr must stage a heroic last stand to defend the Confederation and keep her platoon alive.

~~~~~

Huff has long been recommended to me as a fluffy milSF fix, and after hearing her talk about queer milSF at LonCon3, I decided that, indeed, she might be worth a glance. Titan Books is finally bringing out UK editions of the Confederation/Valour series, so it seemed right to start at the start…

Valour’s Choice is not going to revolutionise the genre. It’s not going to bring a new paradigm to milSF or SF more widely. It’s not crunchily asking huge questions, debating large-scale moral issues, or talking ethics. It’s nothing like Mirror Empire, say. Except in one respect: both are excellent.

Valour’s Choice, as Huff’s afterword discusses, is openly based on the Battle of Rorke’s Drift; right down to the heroic actions of wounded soldiers, the casualties, and the oral war-cries as challenges to the victors. Unfortunately, that extends into Zulu-level portrayals of the antagonists; the Silviss are a savage, brutal, inherently violent species, so using them as stand-ins for the Zulu people is a problematic decision which allows Huff to keep the dramatics and lack-of-seeming-humanity of the attackers of the filmic depiction but doesn’t really alieviate the racism that went with that depiction in the 1960s. However, what Huff does capture is the drama of the battle; the pacy, simple, blunt style on display in the novel really works with what Valour’s Choice is, an adrenaline-pumping action novel.

Of course, milSF is often very interested in the characters, but only of NCOs and below; Huff breaks this mold slightly with Lieutenant Jarrett, whose character developes and is a subject of significant speculation across the novel, but largely focuses on the grunts. Valour’s Choice stars Staff Sergeant Torin, the stereotypical sergeant who knows her troops, knows how far to let things slide but also what needs picking up on, knows how to keep discipline and also to control and manipulate officers. Essentially, Torin is the paradigmatic NCO, and it shows, but also works; Huff makes that into a character, rather than caricature, by virtue of her interactions across different directions. The non-officer Marines are also given personalities; there are a large number of named characters as privates and corporals across Valour’s Choice, and each has distinct attitudes, speech patterns, and personalities, making it a very packed, but never crowded, novel. It’s also notable how interchangable gender is; although essentially binarist, there appear to be no gender distinctions in the Confederacy, and no issues over sexuality – sleeping all kinds of combinations of genders is seen as perfectly normal in an awesomely sex-positive book.

The single greatest achievement of Valour’s Choice, though, is the retention of its humour. As we move into more dramatic and indeed tragic territory, Huff never loses sight of a certain lightness; that lightness is estyablished openly in the prologue with reference to Douglas Adams, and forms a lrge part of the feel of the early novel, giving way slowly to rising tensions. But even in those tense moments, characters and authorial voice both find things to make light of; not only an intensely human response but also a very difficult balance to achieve, and the way Huff threads her humour into the tapestry is expert.

Valour’s Choice is far from unproblematic, given its literal alienisation of the Zulu people; but at the same time it is a fast, fun, and very liberal milSF novel. It’s good to see Titan bringing Huff, and Staff Sergeant Torin Kerr, to a UK audience.