Home » Posts tagged 'homosexual'

Tag Archives: homosexual

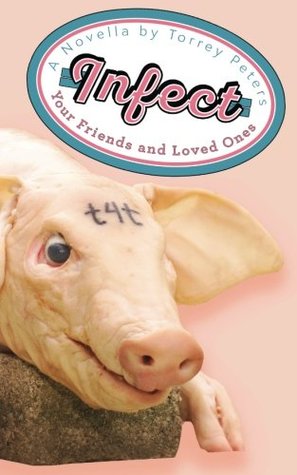

Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones by Torrey Peters

In the future, everyone will be trans.

So says Lexi. She’s a charismatic trans woman furious with the way she sees her trans friends treated by society and resentful of the girl who spurned her love. Now, Lexi has a plan to wreak her vengeance: a future in which no one can produce hormones and everyone must make the same choice that she made—what body best fits your gender?

~~~~~

I first heard about Infect Your Friends And Loved Ones through Helen McClory’s Unsung Letter, specifically Letter 37 by Anya Johanna DeNiro; a novella about trans lives, literalising the transphobic myth of trans as contagion, by a trans woman? I’ll be reading that!

Peters’ novella is a slim volume, barely over 60 pages long; but Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones packs a lot into that space. It’s a story about trans life now, and the trans community; about the toxicity of masculinity, and the cisheteropatriarchy; about the way trans people are treated by society, and the way trans women are fetishised, othered, and attacked. The narrative jumps back and forth around time; so we see trans women in the modern world, marginalised and mistreated by cis men who claim to love them, and in the post-contagion future, where everyone has to choose gender, but trans people are the scapegoats for the problem, blamed (albeit accurately) for its existence.

Peters’ narrative strength rests on its characters. There are two whose interactions colour every part of the narrative; Lexi, and the unnamed narrator, a former friend and lover of Lexi. Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones makes Lexi both charismatic and unlikeable; her passion and dysfunction are incredibly powerful and draw the reader to her strongly, while her willingness to lash out and hurt those around her, and her manipulative nature repels the reader at the same time. This is also true of the self-centred trans woman whose voice the whole story is told in; less charismatic, and more obviously self-centred, she is a frustrating guide to events, with her sense of self-worth so obviously contingent on the approval of those around her. Both characters are incredibly believable and sympathetic, and their growth over the course of the narrative is effective and well written; Peters understands the way people change and develop and puts that in here very effectively.

The worldbuilding is quite slim; Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones has some vague sketches about the impact of everyone having to take hormones all the time, and of government supplying hormones to everyone, although it doesn’t really get into that, beyond looking at the black market supply of hormones to cis people (something that is a reality for many trans people in the present day). Peters isn’t really interested in the effects of the contagion on cis people, or for that matter on intersex people (which, given the premise of the novella, is a rather problematic piece of erasure); she’s really only interested in the effect on trans women.

That erasure of intersex people is symptomatic; Infect Your Friends and Lovers has two types of characters in: cis men, and trans women. No other kind of character gets a look in; cis women are mentioned at most in passing, in relation to husbands or boyfriends, and intersex, nonbinary or trans male people simply don’t exist in the narrative. Peters isn’t interested in their stories, and seems to be saying that solidarity is for trans women; that trans women’s communities are all, and only, about supporting people who identify as women. This doesn’t reflect the trans community I know, nor one I would wish to believe in.

In the end, Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones is an interesting novella, and the emphasis it places on a sense of community is hugely important; but Peters’ erasure of trans people who don’t identify as women is a severe dampener on this whole work.

If you would like to support these reviews, and the trans community, and have a chance at winning a book, all at once, please take a look at this post requesting donations or activism to trans causes.

A Small Charred Face by Kazuki Sakuraba, trans. Jocelyne Allen

What are the Bamboo?

They are from China.

They look just like us.

They live by night.

They drink human lifeblood but otherwise keep their distance.

And every century, they grow white blooming flowers.

A boy name Kyo is saved from the precipice of death by Bamboo, a vampire born of the tall grasses. They start an enjoyable yet strange shared life together, Kyo and the gentle Bamboo. But for Bamboo, communication with a human being is the greatest sin.

~~~~~

Vampires are a mainstay of horror, and have been since before John Polidori wrote The Vampyre in 1819; they’ve also long been a subject for reclamation in fiction, whether in that model or from other cultures. A Small Charred Face caught my eye as another entry in that long tradition of humanising monsters… Kazuki Sakuraba’s book is somewhere between a single novel and three separate, linked novellas collected into one volume; the marketing suggests it be read as one, and so I will review it as such.

A Small Charred Face is fundamentally a wistful, sad set of stories; it is about fading, aging, changing, and memory. The first two parts of the book are very intimate in scale, following single individuals; first, a human child taken in by a pair of Bamboo, who raise him until he becomes an adult; and second, a Bamboo who had befriended him briefly in his childhood, who later took in the child he took in shortly before his own death. They focus in very deeply and intently on the emotional relationships, and the idea of growing up; in the first part, of how a child does not understand the importance of growing up, and in the second, the problem of not growing up while those around one do.

A Small Charred Face is beautiful in both these parts; the characters are so well realised and so deeply, painfully human, in all their flaws, that their fights, their struggles, and their loves are all intensely touching. Watching Kyo age, and realise what he has forgotten, is a profoundly painful experience; while watching Mariko remain a perpetual child, while those around her age and die and maybe even forget her fundamental traumas, is similarly brutal. Sakuraba’s grasp of voice is vital here; the shifting first person narration is not only incredibly individual, but also ages with the characters, and shows their emotional development, in a very real way. Sakuraba’s writing also draws the reader through with great pacing and style, demanding one reads on to find out what happens to these characters, making it a fast book to read, and one hard to put down.

Sakuraba also shows romantic love beautifully; Kyo is raised by Mustah and Yoji, a pair of male Bamboo, and their mutual love and adoration is never shown as a sexual matter, but is shown as utterly pervading everything about them. A Small Charred Face, for half its length, shows some truly beautiful romantic writing; and the confusion of feelings of Kyo towards his adoptive parents is painful and beautiful to behold, as is the way his feelings about his past change and develop.

The third story in A Small Charred Face is rather less strong; it explains how Bamboo society in Japan came to be, in exile from China. Focused on a narrator who is a smart, dedicated, driven member of the royalty of the takezoku (the name the Bamboo called themselves in China), it looks at persecution and at discrimination. Sakuraba takes on a lot of themes across the sixty pages of this story, and tries to grapple with them all; while the despair of a brilliant woman forced into hiding her intelligence because of the needs of society are incredibly moving, other emotional elements don’t ring true, in part because the story is just too rushed, and relies too much on the way it plays on references to events in the future of the story that happened in previous episodes of the book.

In the end, A Small Charred Face reminded me very strongly of Octavia E. Butler’s Fledgling; both intensely emotional and beautiful books using vampires to talk about humanity, Sakuraba’s is much more wistfully sad, but, for the most part, just as brilliant.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

Ruin of Angels by Max Gladstone

The God Wars destroyed the city of Alikand. Agdel Lex has risen in its place. Dead deities litter the surrounding desert and a squidlike tower dominates the skyline—while treasure seekers, criminals, angels, demons, dispossessed knights, grad students, and other fools gather in its ever-changing alleys, hungry for the next big score.

Kai Pohala (last seen in Full Fathom Five) finds her estranged sister, Ley, at the center of a shadowy and rapidly unravelling business deal. When Ley goes on the run, wanted for a crime she most definitely committed, Kai races against time to track her down. But Ley has her own plans, involving her ex-girlfriend, a daring heist out in the god-haunted desert, and, perhaps, freedom for an occupied city.

~~~~~

The Craft Sequence was nominated for the Hugo Awards for Best Series in 2017, for the nonchronological block of five novels that came out between 2012 and 2016. Now, dumping the numerical titles and for the first time releasing a book in immediate chronological succession from that which came before, Max Gladstone returns with Ruin of Angels…

The Craft sequence has always been concerned with economics, with poverty, with religion, with imperialism and empire, with ideas of reality. Ruin of Angels engages with those concepts once again, fiercely; recalling the issues at the centre of Last First Snow, Gladstone draws the reader once again into a world where two different conceptions of reality and how the world should be are locked in a cold war, and something is about to give… Unlike that earlier novel, here, there literally are multiple layers of city; Ruin of Angels recalls China Mieville’s The City and the City, where the practice of knowing which city one inhabits is intensely political. The imperial authority of the Iskari believes in a specific kind of city, Agdel Lex, orderly, regimented, a planned urban metropolis of grids and wide roads, bordering a desert; and in the chaos of the God Wars, it implemented this vision on top of the city of Alikand, leaving that more organically evolved city of libraries in a kind of limbo between existence and not. The way Gladstone plays with these levels of realities, and the way the Iskari use the Rectification Authority (or Wreckers) to enforce their view of the city, feels almost Lovecraftian; certainly the tentacular symbiotes have something of that in their DNA.

Which city you inhabit at any time, which city you believe in, is a political act, and slipping between the realities of the two is a useful criminal survival skill; Ruin of Angels is in many ways a heist novel, or rather a series-of-heists novels, as various characters, most notably Ley and Kai, get in each others’ ways and ruin each others’ plans with the best of intentions. Indeed, Gladstone really captures the sibling rivalry between the two; the relationship between the sisters is at the core of much of what propels and prolongs the plot, as personal and political get entangled and miscommunication and noncommunication lead to disaster. That isn’t to say the plot is necessarily overlong; the way Gladstone propels it, with all its twists and turns, keeps the reader thoroughly engaged in Ruin of Angels, and wondering what happens, although perhaps with a few too many novel-prolonging jumps of point of view and obstacles thrown in. The biggest flaw it suffers comes from Ley’s character; like all heists, it relies on sleight of hand, the problem being that what Ley conceals from those around her, and Gladstone from the reader, raises the stakes of the novel dramatically as it draws to its close and seems to come slightly from nowhere.

Gladstone is always a fantastic character writer, and Ruin of Angels is no exception; that’s the greatest strength of the book, in fact. Kai, who we have met before in Full Fathom Five, sees her character fleshed out more, her realisation of her privileged background really being driven home and the trauma of the events of that novel driven home; Tara likewise continues her development from the hard, cold Craftswoman to someone who really cares and is engaged in a project of improving the world.

The rest of the cast are new, and make a fantastic set of points of view; Ley’s utter determination and refusal to open up to anyone else, to make herself vulnerable, are shown as both strength and weakness, and not the full extent of her character, while her former lover Zeddig is a brilliant, sharp, witty, committed woman who isn’t sure how to feel about her old partner, and gets caught up anyway. Relationships and their complexities are one of the hearts of Ruin of Angels; the way Gal and Raymet dance around their feelings is almost soap operatic in the way it is prolonged, and the way Gladstone uses their contrasting personalities to set up a beautiful romance pays off fantastically. Even the lesser characters who people Ruin of Angels are vividly written, from the vile agent of the Iskari, Bescond, to the perpetually high investments manager Fontaine, through the trans space-start-up ultra-rich visionary futurist (yes, Gladstone put Elon Musk in his novel… and made him trans); more than just broad brushstrokes, Gladstone gives them full personalities, in part by hinting at them around the edges of those strokes.

This number of characters introduces another innovation for the Craft Sequence to Ruin of Angels; in a book of less than six hundred pages, there are nearly eighty chapters, and each one is from the point of view of a different character, in some cases multiple characters. This is vitally important in giving us different perspectives on the events of the novel, and indeed the characters, at earlier stages; seeing how Kai and Zeddig see each other, for instance, is a wonderful piece of writing. However, especially as the action gets faster and Ruin of Angels moves towards its climax, it gets rather choppy and draws out the action and cliffhangers in a way that moves from powerful towards frustrating as Gladstone barely gives full scenes before cutting away.

Ruin of Angels marks something of a break for the Craft Sequence: less economic in scope, more concerned with naked power; more head-hopping and with a larger cast. But it still has the same essentially hopeful tone, the same flashes of brilliant humour, and the same excellence as ever; I highly commend Max Gladstone’s work to you, and think this continues the series in exceptional form.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

Taste of Marrow by Sarah Gailey

A few months ago, Winslow Houndstooth put together the damnedest crew of outlaws, assassins, cons, and saboteurs on either side of the Harriet for a history-changing caper. Together they conspired to blow the dam that choked the Mississippi and funnel the hordes of feral hippos contained within downriver, to finally give America back its greatest waterway.

Songs are sung of their exploits, many with a haunting refrain: “And not a soul escaped alive.”

In the aftermath of the Harriet catastrophe, that crew has scattered to the winds. Some hunt the missing lovers they refuse to believe have died. Others band together to protect a precious infant and a peaceful future. All of them struggle with who they’ve become after a long life of theft, murder, deception, and general disinterest in the strictures of the law.

~~~~~

Back in June, I reviewed River of Teeth, the debut novella from Sarah Gailey; this review of the sequel will inevitably contain SPOILERS for the previous installment in the series.

Taste of Marrow is Hippopeople 2: This Time It’s Personal. Whereas River of Teeth was very much a heist novel with hippos, motivated largely by greed albeit with a personal grudge in there providing an underlying motivation and narrative for Houndstooth, this time, Gailey has given us a book that is purely about the personal, for every character; the intensity and darkness are turned up a few notches from the first novella, and it shows throughout the whole piece.

There are two plots to Taste of Marrow, coming together as the novel progresses and innately linked; the first is of Adelia and Hero, who believe Houndstooth and Archie dead in the events at the dam at the close of River of Teeth, caring for Ysabel, Adelia’s baby. The second is Houndstooth and Archie, knowing Adelia is alive and believing she somehow abducted Hero, obsessively searching for them. Arguably, this novella is about love, and the lengths people will go to for it; the literal insanity that Houndstooth’s obsession with finding Hero drives him to, and the extreme risks to which Adelia will go for Ysabel – right up to self-sacrifice, never losing sight of the centrality of the welfare of her baby. Contrasting that are Hero’s attempts to deal with their grief at the (supposed) death of Houndstooth, and Archie’s much more pragmatic love of US Marshal Carter; the four different loves drive the novella completely, and Gailey paints each of them sympathetically, although her greatest affection clearly lies with Archie herself.

The way Gailey carries off this complex two-strand plot is a little less solid. Taste of Marrow doesn’t really explain why months have passed (enough, after all, for Adelia to give birth and Ysabel to grow somewhat) since the events of River of Teeth while much of its cast has remained in, essentially, stasis; nor does she give much thought to how the events which push this second work into motion actually, practically speaking, come about. But once those are overlooked, this is a fast-paced dual-strand novella; the alternating chapters of Taste of Marrow leave the reader on permanent cliffhangers and work to increase and boost the tension, and the way the narratives mirror each other is craftily and well done.

It’s also worth noting that this is almost a more visceral novella than the previous one in the series; while both are sometimes described as horror because of the violence of the hippopotami, Taste of Marrow is actually more brutal in its violence, with two rather explicit torture scenes (by the protagonists). These fit with the plot and with the characters, but Gailey really layers and lingers more on the violence and blood here than in scenes of more general carnage, an interesting choice.

Despite a rough start, then, Taste of Marrow is a fantastic book with a really solid emotional core; Gailey has definitely gone in a darker direction for this book, but she’s made that work.

Disclaimer: Sarah Gailey is a friend. This review was based on an ARC of the novel provided, on request, by the publisher. Taste of Marrow will be released on September 12th.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

Provenance by Ann Leckie

Following her record-breaking debut trilogy, Ann Leckie, winner of the Hugo, Nebula, Arthur C. Clarke and Locus Awards, returns with a thrilling new story of power, theft, privilege and birthright.

A power-driven young woman has just one chance to secure the status she craves and regain priceless lost artefacts prized by her people. She must free their thief from a prison planet from which no one has ever returned.

Ingray and her charge will return to their home world to find their planet in political turmoil, at the heart of an escalating interstellar conflict. Together, they must make a new plan to salvage Ingray’s future, her family, and her world, before they are lost to her for good.

~~~~~

Never has a novel been so accoladed as Ancillary Justice was in the science fiction community. Never has a trilogy received quite so much love and critical acclaim as the Imperial Radch books did. Two years after the release of the last volume in that series, Ancillary Mercy, Ann Leckie has returned to what I’m calling the Presgerverse with a new novel, Provenance…

Provenance is a high-stakes political heist novel, on its face, that morphs through a series of other forms, including whodunnit, to something akin to a spy thriller by the end of the book; Leckie takes a simple plot, throws in a few curveballs (including a good murder, of course), and emerges with a complex and compelling narrative taking in issues of family, of imperialism, of political manipulation, of tradition, and of the very idea of value itself. Which all sounds rather highbrow, but Provenance also never loses sight of itself as a fun book; this is a novel which cracks jokes, and has the reader laughing aloud (a piece of translation software renders swearwords as things like “fiddlesticks”, cutting the tension at a crucial point in the novel). The tension is slowly built up through making clear the rising personal and political stakes involved in the novel, as they tie together in a very deft way; and the climax ties everything up surprisingly neatly and with an excellent emotional catharsis for the characters that Leckie has very much earned.

Much of the strength of Provenance is in those characters; Leckie really brings her varied and broad cast to life. The novel is narrated in third-person, from the perspective of Ingray, a young woman fostered by a prominent family in Hwae; the way fostering works plays a key role in the novel, and is somewhat reminiscent of Roman Imperial adoptions. Ingray is an interesting character, with low self-confidence, who is also something of a young adult novel archetype; indeed, at a couple of points, Leckie hangs a lampshade on her tendency to pluck, in the nick of time, a brilliant plan out of the air after panicking about it. The rest of the cast are rather less easy to peg onto any adapted archetype, especially Garal Ket, a neman who uses the pronoun e; Provenance never really explains its gender system, but gender neutral neopronouns appear on the second page, and are simply an accepted part of society, with various characters, including background figures, representing a range of genders.

The worldbuilding in Provenance is at times its weakest point, for a related reason: Leckie clearly knows this world and this system, but is only presenting relevant information – and at times, that leaves the book feeling a little messy, because what the reader sees as relevant information can go beyond what the author does. This is especially true in trying to understand the social and political system of Hwae; Leckie gives us a lot of pieces of the puzzle, but in the end not enough to really put the whole thing together, especially when it comes to the non-Hwae polities we meet who play pivotal roles in the plot.

Whereas the Imperial Radch trilogy was a triumph of serious space opera, Provenance is much more straightforwardly fun; it may be engaging with huge, important themes, but it never loses sight of the necessity of a sense of humour. Ann Leckie proves, here, that there is far more than one string to her quill.

Disclaimer: Ann Leckie is a friend. This review was based on an ARC of the novel provided, on request, by the author. Provenance will be released on September 26th.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

The Black Tides of Heaven by JY Yang

Mokoya and Akeha, the twin children of the Protector, were sold to the Grand Monastery as children. While Mokoya developed her strange prophetic gift, Akeha was always the one who could see the strings that moved adults to action. While his sister received visions of what would be, Akeha realized what could be. What’s more, he saw the sickness at the heart of his mother’s Protectorate.

A rebellion is growing. The Machinists discover new levers to move the world every day, while the Tensors fight to put them down and preserve the power of the state. Unwilling to continue to play a pawn in his mother’s twisted schemes, Akeha leaves the Tensorate behind and falls in with the rebels. But every step Akeha takes towards the Machinists is a step away from his sister Mokoya. Can Akeha find peace without shattering the bond he shares with his twin sister?

~~~~~

On Monday, I reviewed JY Yang’s The Red Threads of Fortune; today, I’m here with the other half of this initial duology in the world of the Tensorate, The Black Tides of Fortune. These reviews are up in this order because that’s the order I chose to read these two apparently standalone novellas.

Unfortunately, that’s not the order these novellas need to be read in. The Black Tides of Heaven ends in the same emotional place that The Red Threads of Fortune begins, approximately; the rebellion by Akeha against his mother, the tragic events of Mokoya’s life coming to their head, et cetera. Yang builds the world brilliantly in this novella, and really gets their ideas across; things referenced in Red Threads of Fortune are put centre-ground in The Black Tides of Heaven in a way that makes them much more explicable, such as Mokoya’s history as a prophet, the relationship between Protectorate, Grand Monastery, Tensorate, and Machinists, and the relationship between Akeha and his sister. That’s not done through infodumping; it’s backgrounded in Red Threads of Fortune because, fundamentally, it is the plot here.

This is very much a coming of age story; told in a series of sections focused on Akeha’s relationships with different characters, including his sister, his mother, and his lover, it’s an interesting lens through which to view Akeha’s journey through life. The Black Tide of Heaven really does do a lot of work on personal rebellion and political rebellion, looking at how they’re linked in the case of the Protector’s child, Akeha, and what that means for his actions. Yang uses other characters to give Akeha more roundness, through his reactions to and interactions with them, but without ever making them solely serve him: they all have lives of their own and motives of their own, which often Akeha is subordinated to.

While The Red Threads of Fortune is about personal feelings, told through a political lens, The Black Tides of Heaven very much reverses that; told through a lens of personal feelings and personal impact, Yang is incredibly engaged with ideas around politics. There is a theme of class struggle running throughout the novella, whether of the Gauri against the dominant (and, in a narrative focusing on them, unnamed) race, of those who can’t manipulate the magical Slack against the dominance of those who can, or religious repression of the Observant, a religion who seem very similar to Islam and are written sensitively and from a place of deep familiarity. The politics aren’t the kind where Yang delivers a monologue using a character as a mouthpiece, but where they’re baked into the world, and acknowledged as political choices.

Finally, one of the most interesting things Yang delves more deeply into in The Black Tides of Heaven is the system of gender in the Protectorate, a subject of obvious relevance to this blog. Children have no gender until they undergo a confirmation ceremony, at which they choose a gender, completely unrelated to physical sex, and are then “confirmed” in that gender by procedures and medication that are roughly analogous to sex reassignment surgery. Yang, and their characters, use the pronoun “they” for children who haven’t been confirmed, and we see the confirmation process through both Mokoya’s eyes (she talks about having always felt like a girl) and Akeha’s, who hasn’t really considered it before; the process is a fascinating one, made all the more so by a later character who it reveals binds his breasts because while being male, he did not feel his body needed to be changed. It’s a brilliant and innovative look at gender and ideas of transness, and Yang, themself a nonbinary person, really must have brought their own feelings on gender into play; I certainly as a nonbinary reader found it incredibly engaging and thoughtful.

I rather wish I’d read The Black Tides of Heaven and The Red Threads of Fortune in the opposite order to that which I did, since The Black Tides of Heaven is obviously intended as the first of the pair; I’d have gotten a lot more out of them. Given how incredibly excellent they both are, though, and how much I did get out of JY Yang’s paired novellas, I cannot commend them to you highly enough.

Disclaimer: JY Yang is a friend. This review is based on an ARC from the publisher, Tor.com.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

Bearly A Lady by Cassandra Khaw

Zelda McCartney (almost) has it all: a badass superhero name, an awesome vampire roommate, and her dream job at a glossy fashion magazine (plus the clothes to prove it).

The only issue in Zelda’s almost-perfect life? The uncontrollable need to transform into a werebear once a month.

Just when Zelda thinks things are finally turning around and she lands a hot date with Jake, her high school crush and alpha werewolf of Kensington, life gets complicated. Zelda receives an unusual work assignment from her fashionable boss: play bodyguard for devilishly charming fae nobleman Benedict (incidentally, her boss’s nephew) for two weeks. Will Zelda be able to resist his charms long enough to get together with Jake? And will she want to?

Because true love might have been waiting around the corner the whole time in the form of Janine, Zelda’s long-time crush and colleague.

What’s a werebear to do?

~~~~~

From the terrible dad-joke of the title through the back copy, I was always going to be interested in Bearly A Lady, even if it hadn’t been by Cassandra Khaw and put out by the Book Smugglers as part of an initiative I want to support. As it was, those factors all aligned beautifully, making this a very easy purchase decision…

Bearly A Lady is a slightly odd book; it’s chick lit, something Khaw discusses in her essay in the back about her influences in writing it, but it’s also very much not: it’s almost a send-up of chick lit in the way it uses the tropes of that genre and the conventions that it is playing with. Simultaneously, it’s subverting and embracing urban fantasy; whereas much UF is about a mystery or a supernatural threat, Bearly A Lady is about finding a date, and brings in other tropes of the genre along the way to that goal. What results is something that should be a light, frothy read, that carries far more substance than it should.

Bearly A Lady takes a lot onto its shoulders, not least of which is fatphobia; much of Zelda’s character, and her interactions with the world around her, are driven by reactions to her size. As a werebear, Zelda is a large woman – impressively, powerfully large, in her eyes and those of the reader, disgustingly fat to many background figures. Khaw excels in drawing out different manifestations of fatphobia, from treatment in restaurants and on public transport to casual comments from those around one, whilst also maintaining Zelda’s awareness of her size and a brilliant fat-positive attitude in the narrative.

That strength of empathy in the depiction of fatphobia carries over more broadly to the way Khaw writes Zelda. Bearly A Lady is one woman’s story, very much so; Khaw brings a sensitive and intelligent hand to Zelda’s issues with romantic anxiety, distress over competing emotional attachments and affections, and especially her (rather strong) crush on co-worker Janine. Zelda pops off the page beautifully, from her very first appearance through to the final line of her voice signing off at the end of the book; Khaw really brings her to life. The rest of the cast vary largely depending on gender; the women are all brought to life quite fully and well, even those who only appear briefly getting a strong backstory. The men, on the other hand, come off less well; the three romantic entanglements of Zelda are all, in different ways, creeps, and two-dimensional creeps, and Khaw doesn’t waste her time on giving them more characterisation than that, a powerful decision in contrast to too much (especially genre) fiction which emphasises its male characters at the expense of women.

As a genre, romance often gets a lot of criticism for the way it treats consent, and Bearly A Lady is very actively engaged in that criticism. Khaw treats consent seriously, not just in sex but in discourse generally, and anything that pushes the boundaries of consent is clearly inappropriate and problematised as such; this isn’t handled in a moralistic way, but as something that is simply part of the story and part of Zelda’s life. It crops up at work, in her social life, and inevitably in her romantic and sexual life; and the way characters deal with issues of consent is a key marker of whether we should sympathise with them or not, the way Khaw writes.

Khaw is generally strongest at character work; the plot of Bearly A Lady feels slightly like a series of anecdotes that she wanted to work into the novella, strung together a little haphazardly. The story goes from a to b adequately, but with a series of jump cuts and coincidental happenings that really frustrate. Many individual scenes are beautiful little moments that stand alone and crystalise all sorts of things out of the rest of the story; however, Bearly A Lady falls down on flowing between them. There’s a kind of disconnect that makes it feel like the novella was written as a series of stories, not a single narrative, and the joins aren’t quite smooth.

Finally, it would be a major omission not to discuss the humour that is a key component of Bearly A Lady. Khaw’s sense of humour is an incredibly important component in her work; the title onwards, this novella is no exception, and has a number of different forms of it. One of the most significant is the wry aside, such as her description of small talk as “the last bastion of the beleaguered British person”; these moments of cutting insight are delivered with a light tone that really works.

Bearly A Lady isn’t a perfect book, but it is one I heartily recommend, not just for its politics and the deft way Khaw works them in, but also for the absolutely brilliant characterisation and flashes of humour throughout the story.

Disclaimer: Both the author, Cassandra Khaw, and the publishers, the Book Smugglers, of this novella are friends of mine.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

The Red Threads of Fortune by JY Yang

Fallen prophet, master of the elements, and daughter of the supreme Protector, Sanao Mokoya has abandoned the life that once bound her. Once her visions shaped the lives of citizens across the land, but no matter what tragedy Mokoya foresaw, she could never reshape the future. Broken by the loss of her young daughter, she now hunts deadly, sky-obscuring naga in the harsh outer reaches of the kingdom with packs of dinosaurs at her side, far from everything she used to love.

On the trail of a massive naga that threatens the rebellious mining city of Bataanar, Mokoya meets the mysterious and alluring Rider. But all is not as it seems: the beast they both hunt harbors a secret that could ignite war throughout the Protectorate. As she is drawn into a conspiracy of magic and betrayal, Mokoya must come to terms with her extraordinary and dangerous gifts, or risk losing the little she has left to hold dear.

~~~~~

JY Yang is one of the voices in the genre fiction community I always want to hear more from: intelligent, angry, nonbinary, queer, not white or Western. Imagine my delight when I discovered that I could hear from them in not one, but two novellas this autumn; and imagine my greater delight when Tor.com sent me ARCs of the pair of them… today I’ll review The Red Threads of Fortune, and on Thursday I’ll review the simultaneously released companion volume, The Black Tides of Heaven.

Silkpunk is a relatively meaningless genre descriptor, seeming to apply to everything with an East Asian influence on it; but The Red Threads of Fortune really does seem to solidly fit into the silkpunk designator. Not only is Yang using strongly East Asian influenced cultures as a starting point from which to build their secondary world, but they’re also using the political side of the silkpunk label; The Red Threads of Fortune is heavily engaged in discussions of, and resistance to, systems of various kinds, and is in dialogue with real world racism and assumptions. There’s a theme of resistance to authority, and of the way some authority collaborates in or overlooks resistance to higher authority; there’s a theme of personal relationships having political impacts; and so on, all fascinating and thought through. None of this is heavy-handed; instead, Yang makes them essential to the plot and world, seeding their themes throughout the novella, and rarely taking sides on the issues they raise but making it clear that these are issues to be considered.

That could suggest The Red Threads of Fortune is a very intellectual story, more of a thought piece than anything with emotional resonance. That’s very much not the case. Yang’s plot is built around heartbreak, love, resentment, and emotion; this isn’t a book about politics, really, but about the human heart. Specifically and mainly, the human heart of our protagonist, Sanao Mokoya. Mokoya has suffered the heartbreak of the death of her daughter, in a move that superficially resembles the opening of The Fifth Season, but has a completely different emotional reaction; Yang doesn’t pull punches, and Mokoya’s depression and grief are bluntly portrayed. However, Yang isn’t brutal either, and Mokoya isn’t a caricature of sadness; she is a complex, rounded, interesting character, one whose every interaction is coloured by the loss of her daughter but also by the way her mother raised her, and by her love life, and her emotional ties. Yang gives us a rounded and full emotional character to really connect to, even when she finds it hard to connect to others.

Around Mokoya, Yang arranges a number of other similarly complex characters; her twin, her husband and the father of her daughter, the person she has worked with since running away from her husband in the wake of the tragic death of her daughter, and most interestingly, Rider. Rider is a nonbinary character of a different racial and cultural background to the rest of the characters, and The Red Threads of Fortune relies heavily on emotionally connecting with them as well as with Mokoya; Yang really builds on and uses their relationship, and the way it develops, in a beautiful, powerful, and sweet way, without ever making it untrue. There are bumps and problems between them, and the emotional truth of the negotiation of the relationship is brilliantly moving.

Themes and characters don’t make a plot, necessarily. The Red Threads of Fortune slightly falls down on this front; the core plot is simple, and effective, and self-contained, with brilliant emotional resonances. The monster-hunting transitioning into politicking is brilliant, and the way Yang ties personal grief and responses to that into the plot is fantastic. It’s fast-paced and the romance feels very true. However, the way Yang ties the story into a wider world doesn’t feel complete; the references are obviously intended to be meaningful, but they don’t actually connect with the reader on the terms of The Red Threads of Fortune alone, and that takes some of the force of the story away.

The strengths of The Red Threads of Fortune more than makes up for the weaknesses; this is among the most beautiful and most deeply human books I’ve read in some time, and JY Yang is a truly fantastic talent whom I will follow wherever they lead.

Disclaimer: JY Yang is a friend. This review is based on an ARC from the publisher, Tor.com.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.