The Fisher of Bones by Sarah Gailey

The Prophet is dead.

The eyes of the Gods have turned to his daughter. But she isn’t ready. Not for the whispers in her ear, for the divinations… for the blood. Her people’s history and their future, carved by ancients into the bones of long dead behemoths, are now her burden. Only she can read them, interpret the instructions, and guide them to the Promised Land.

Their journey is almost at an end, but now, without the Prophet, she must find a way to guide them to the place they will call Home. Through blood and through sand, against the will of her own flock, against the horrors that haunt the darkness, only she can bring her people Home.

The Prophet is dead. Long live the Prophetess.

~~~~~

I’ve already reviewed Sarah Gailey’s American Hippo duology on the blog, so the author needs no real introduction; The Fisher of Bones was published for free in serialised form at the fantastic Fireside Fiction, as well as in a collected edition that came out halfway through the serialisation; this review is of the collected volume.

The Fisher of Bones is essentially a religious novella; it is about Fisher, who has taken the place of her father, Fisher, as the prophet of the Children of the Gods leading them from a secular land which has banished its divinities to a Promised Land described in revealed scriptures on the bones of extinct creatures. The plot describes the journey from the point at which Fisher’s father dies to the arrival at the Promised Land; along the way, the pilgrims meet and bring into their ranks outsiders, lose members, and have to deal with logistical problems. And then, of course, they arrive.

The simplicity of the plot is a strength, given what Gailey is really concerned with in The Fisher of Bones: faith and authority. Fisher is, after all, a new prophet to her flock, and Gailey deals with some of the consequences of that, such as the mistrust attendant upon her among some and the lack of faith in her ability to lead. The different manifestations of religious faith are also brilliantly handled; Fisher’s essentially nonhierarchical faith running up against the increasing idea of a hierarchy among some of her flock, for instance, or the way Fisher’s attitudes, and those of others, are permeated by the sense that everything the gods give is a positive gift, even if it is not always immediately apparent as such. The handling of faith is very sensitive and intelligent, and Gailey really embraces the centrality of it to her characters and plot.

The other big theme Gailey deals with is fertility and blood. The Fisher of Bones is one of the few stories centring a woman where periods play pivotal roles in the plot and emotional development of the story; in different ways, and at different times, characters’ periods or lack thereof is key. Similarly, Fisher’s pregnancy is brilliantly described, although the mysticism around her giving birth is a little frustrating; the physicality of the fertile womb is wholly embraced in Gailey’s writing and shown with a rare bluntness.

That isn’t to say The Fisher of Bones is simply a dry exploration of big themes. Fisher is a fascinating character, as is her friend Naomi; both are practical women with faith, whose practicality, faith and friendship can put them at odds or in alliance. The way the two are developed and written across the course of the novella is fascinating and beautiful. Unfortunately, they’re the only two particularly solid characters; the closest to another we see is Marc, the husband of Fisher, whose character is rather two dimensional and undergoes a dramatic revelation part way through to become a very different, equally two dimensional character, with little discussion of the effect of that on the relationship between the two characters.

The Fisher of Bones packs perhaps its best punch at the very close of the novella; Gailey fantastically turns everything upside down in a wholly unexpected way, and reconfigures everything that has come before. To say too much would be to spoil the impact of a brilliant close, though, to a novella that, while not as good as some of her other work, is still a brilliant piece of writing from an excellent author.

Disclaimer: Sarah Gailey and Pablo Defendi, publisher of Fireside Fiction which published Fisher of Bones in both serialised and collected forms, are both friends of the reviewer.

If you would like to support these reviews, and the trans community, and have a chance at winning a book, all at once, please take a look at this post requesting donations or activism to trans causes.

The Stone In The Skull by Elizabeth Bear

The Gage is a brass automaton created by a wizard of Messaline around the core of a human being. His wizard is long dead, and he works as a mercenary. He is carrying a message from a the most powerful sorcerer of Messaline to the Rajni of the Lotus Kingdom. With him is The Dead Man, a bitter survivor of the body guard of the deposed Uthman Caliphate, protecting the message and the Gage. They are friends, of a peculiar sort.

They are walking into a dynastic war between the rulers of the shattered pieces of a once great Empire.

~~~~~

Returning to the world of completed series seems to be popular in fantasy at present; Tad Williams has returned to Osten Ard, K. W. Jeter has returned to steampunk London, and Elizabeth Bear has returned to the world of the Eternal Sky once more, and to characters from her story ‘The Ghost Makers’ in Fearsome Journey…

The Stone in the Skull takes place in the same world as the Eternal Sky trilogy, but in a different part of that world; we’ve moved south from the events of the earlier trilogy, and later, to the Lotus Kingdoms, some years after the fall of the Uthman Caliphate in Shattered Pillars. Bear takes us from one place to the other with a certain knowingness; the start of the novel sees the Dead Man and the Gage travelling south from Messaline to the Lotus Kingdoms bearing a message, and that journey is also, of course, the journey the reader is taking. It’s a very well done transition, and the journey itself, as well as being a cliche of the genre, also allows the reader to get a different view of the Lotus Kingdoms than is presented from the monarchs’ viewpoints.

If there’s a problem of the worldbuilding, it’s the timeline. The Stone in the Skull, especially in combination with ‘The Ghost Makers’, reads as if it has a very inconsistent historical chronology; timescales shift and blur, relations and family trees compress and expand in strange ways, and the novel seems to have a chronology that feels mythical in its blurriness rather than the more historical feel the rest of the novel gives its history.

The Stone in the Skull has four main viewpoint characters; the Dead Man and the Gage alternate chapters with two of the rajnis of the the Lotus Kingdoms: Mrithuri, the unmarried young rajni of Sarathi-lae, the richest kingdom, surrounded by the others; and Sayeh, mother, widower, and shandha (essentially, a trans woman), rajni of Ansh-Sahal, the poorest of the kingdoms. The four different perspectives on the Lotus Kingdoms and the world more broadly allow for a wider understanding of things, especially as the different religious approaches of the Dead Man and the native inhabitants of the Lotus Kingdoms are so variant.

The other strength this central cast gives to The Stone in the Skull is the diversity of voices. Bear has always been excellent at characterisation, and this novel is no exception; from the cynical worldweariness of the Gage through to the blunted youth of Mrithuri, from the emptiness and faith of the Dead Man to the absolute maternal devotion of Sayeh, these four characters have different but in some ways similar drives, and different voices and personalities. They’re easily distinguished, and their different views on the same events are fascinating.

The Stone in the Skull‘s brilliant cast goes beyond its four viewpoint characters; the servants of the various monarchs we encounter, the caravan members Gage and the Dead Man guard on their journey to the Lotus Kingdoms, all are human characters with a good deal of interiority we see hinted at, and their own agendas. Some of the characters’ hidden agendas feel like they’re hinted at very strongly only to be subverted, whereas others have agendas that are much more straightforwardly open, but none are without agenda.

Bear has very few straightforwardly evil characters; unfortunately, both of those who are are the two people with disabilities in The Stone in the Skull, the two rajas of the other Lotus Kingdoms vying to reunify them. Both are caricatured, and their representation is singularly unsympathetic; they may gain interiority later in the series, but at this point both are simply evil, from the points of view from which we have seen them, in one case to the point of cartoonish.

Finally, The Stone in the Skull is another showcase for Bear’s continuing excellence with prose. From the boredom and excitement of the start of the novel, through the rising tensions and complex politics of the body of the book, to the climactic moments of the end, the pacing is fantastic, and the flow of the prose fits the shape of events and the reactions of our viewpoint characters to them perfectly. This book draws the reader in deeply and hard.

I’m hoping later books in the series make the villains less two dimensional and less frustratingly caricatured, but even with that criticism, The Stone in the Skull is an absolutely fantastic epic fantasy from a master of the genre.

Disclaimer: Elizabeth Bear is a friend. I am one of her Patreon patrons.

If you would like to support these reviews, and the trans community, and have a chance at winning a book, all at once, please take a look at this post requesting donations or activism to trans causes.

When The Moon Was Ours by Anna-Marie McLemore

To everyone who knows them, best friends Miel and Sam are as strange as they are inseparable. Roses grow out of Miel’s wrist, and rumors say that she spilled out of a water tower when she was five. Sam is known for the moons he paints and hangs in the trees and for how little anyone knows about his life before he and his mother moved to town. But as odd as everyone considers Miel and Sam, even they stay away from the Bonner girls, four beautiful sisters rumored to be witches. Now they want the roses that grow from Miel’s skin, convinced that their scent can make anyone fall in love. And they’re willing to use every secret Miel has fought to protect to make sure she gives them up.

~~~~~

When The Moon Was Ours had come to my attention even before it won the 2016 Tiptree Award, given that Anna-Marie McLemore’s novel features trans characters, immigrant characters, and magical realism; the Tip win just raised its profile for me, and I’ve finally gotten around to reading it…

When The Moon Was Ours is one of those books that really speaks to me as a trans reader. McLemore’s narrative isn’t solely concerned with trans narratives, though one of the central characters is an immigrant mixed-race trans boy (a kind of character we see all too rarely in fiction generally and speculative fiction particularly); but it’s the narrative of transness that really spoke to me, so it’s where we’ll start. McLemore threads throughout the novel the way Samir feels about his body, and about his gender; When The Moon Was Ours talks about gender dysphoria and the disconnect trans people can feel from their bodies, as well as the way some embrace theirs. It talks about the social stigma towards trans people, and how we internalise that, and how that shame manifests in our self-image. It talks about trans people’s sexuality, about the conflict or congruence between anatomy and emotion. McLemore really cuts through the normal cliches of a trans story, and instead tells something true, recognisable, and because of it, heartbreaking.

This is a book that is about much more than its trans protagonist, though. When The Moon Was Ours also has a cis female protagonist, marked as different from her community by her origin (falling out of a water tower) and by the roses that grow from her wrist. Miel has a tragic backstory, which is slowly revealed over the course of the book; as well as a present which has both its beauties, like her mother-figure Aracely, and her romance with Samir, and its threats, like the Bonner sisters. These aren’t contradictory, although they are in tension at times; it’s the tension that gives rise to the story, and McLemore plays it perfectly, with the teenage emotionality given free rein to really be extreme and powerful.

Every character in When The Moon Was Ours has their struggle; there are only really eight major characters – Samir, Miel, Samir’s mother, Aracely, and the Bonner sisters – but most of the minor characters, such as the Bonner parents and Miel’s own parents, are fleshed out as well. Those we encounter once tend to be a little more one-dimensional and simplistic, but they are really props for the eight core members of the cast to interact with and around; those eight members are intensely real and human, each with secrets of their own, and with their own different, difficult pasts and mysteries.

If When The Moon Was Ours has a flaw, it’s in the way it deals with its magical realism. While some aspects – the rose, for instance – are beautiful and powerful, others seem more laboured, and drawn out; the glass pumpkins of the Bonner farm are strange and beautiful, but little more than a pretty symbol, and a metaphor that really wasn’t necessary and didn’t add anything – or get meaningfully addressed, leaving McLemore’s idea a little half-baked. This is a tendency throughout the book, where symbolism trumps anything else, just layering it on without consideration for what that would actually mean for the characters, or anything else.

This is slightly undercut by the prose of the novel. McLemore’s style is very poetic and flowing; When The Moon Was Ours isn’t told as mimetic fiction, which means some of the disjoints, and some of the excessively-heavy, underbaked symbolism isn’t too jarring, because the novel as a whole treats itself as a piece of folklore. There are references, which feel at times a little too self-conscious, to the way Miel and Samir have become myth in the village; the novel tends to forget those between times, and while poetic, is essential a straightforward fabulist narrative. The mixed approach weakens the effect of either of these styles a little, although the language is still beautiful and penetrating.

In the end, though, When The Moon Was Ours tore my heart out and handed it to me on a platter as a bare, naked, vulnerable, beautiful thing. If you’re trans, it may well do the same for you. McLemore has written a fantastic, beautiful romance, and one well worthy of her Tiptree win.

If you would like to support these reviews, and the trans community, and have a chance at winning a book, all at once, please take a look at this post requesting donations or activism to trans causes.

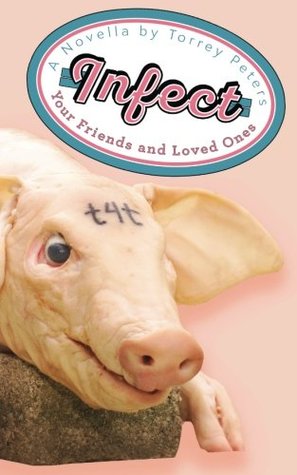

Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones by Torrey Peters

In the future, everyone will be trans.

So says Lexi. She’s a charismatic trans woman furious with the way she sees her trans friends treated by society and resentful of the girl who spurned her love. Now, Lexi has a plan to wreak her vengeance: a future in which no one can produce hormones and everyone must make the same choice that she made—what body best fits your gender?

~~~~~

I first heard about Infect Your Friends And Loved Ones through Helen McClory’s Unsung Letter, specifically Letter 37 by Anya Johanna DeNiro; a novella about trans lives, literalising the transphobic myth of trans as contagion, by a trans woman? I’ll be reading that!

Peters’ novella is a slim volume, barely over 60 pages long; but Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones packs a lot into that space. It’s a story about trans life now, and the trans community; about the toxicity of masculinity, and the cisheteropatriarchy; about the way trans people are treated by society, and the way trans women are fetishised, othered, and attacked. The narrative jumps back and forth around time; so we see trans women in the modern world, marginalised and mistreated by cis men who claim to love them, and in the post-contagion future, where everyone has to choose gender, but trans people are the scapegoats for the problem, blamed (albeit accurately) for its existence.

Peters’ narrative strength rests on its characters. There are two whose interactions colour every part of the narrative; Lexi, and the unnamed narrator, a former friend and lover of Lexi. Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones makes Lexi both charismatic and unlikeable; her passion and dysfunction are incredibly powerful and draw the reader to her strongly, while her willingness to lash out and hurt those around her, and her manipulative nature repels the reader at the same time. This is also true of the self-centred trans woman whose voice the whole story is told in; less charismatic, and more obviously self-centred, she is a frustrating guide to events, with her sense of self-worth so obviously contingent on the approval of those around her. Both characters are incredibly believable and sympathetic, and their growth over the course of the narrative is effective and well written; Peters understands the way people change and develop and puts that in here very effectively.

The worldbuilding is quite slim; Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones has some vague sketches about the impact of everyone having to take hormones all the time, and of government supplying hormones to everyone, although it doesn’t really get into that, beyond looking at the black market supply of hormones to cis people (something that is a reality for many trans people in the present day). Peters isn’t really interested in the effects of the contagion on cis people, or for that matter on intersex people (which, given the premise of the novella, is a rather problematic piece of erasure); she’s really only interested in the effect on trans women.

That erasure of intersex people is symptomatic; Infect Your Friends and Lovers has two types of characters in: cis men, and trans women. No other kind of character gets a look in; cis women are mentioned at most in passing, in relation to husbands or boyfriends, and intersex, nonbinary or trans male people simply don’t exist in the narrative. Peters isn’t interested in their stories, and seems to be saying that solidarity is for trans women; that trans women’s communities are all, and only, about supporting people who identify as women. This doesn’t reflect the trans community I know, nor one I would wish to believe in.

In the end, Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones is an interesting novella, and the emphasis it places on a sense of community is hugely important; but Peters’ erasure of trans people who don’t identify as women is a severe dampener on this whole work.

If you would like to support these reviews, and the trans community, and have a chance at winning a book, all at once, please take a look at this post requesting donations or activism to trans causes.

Trans Day of Remembrance & Giveaway

Today is Trans Day of Remembrance, the day on which we remember the trans people killed in the last year out of hatred, prejudice, and societal violence. This is its eighteenth year, since the first, in 1999, memorialised Rita Hester’s murder. The list of the dead whom we will be remembering from the last year, a sadly necessarily incomplete list because these are only the names we hear about, can be found here.

Today, I am going to a memorial to these dead from our community. I am going to make sure I do not forget them, that they are remembered, and that they are remembered not by dead names and misgendering pronouns, but for who they truly were; for the people who they were murdered for being.

Every year, there’s a long list of names, too many of them trans women of colour, who suffer the intersectional violences of misogyny, transmisia, and racism; too many of them sex workers, who suffer the marginalisation society forces on them. Next year, I want the list to be shorter, and I want your help to make that happen: to make a better world for trans people.

I’m going to give away five signed copies of CN Lester’s book Trans Like Me (reviewed here) in a fortnight. If you want to a chance to get a copy, it’s reasonably simple for you, but potentially life-saving for others.

There are two ways to enter: You can write to or call your local representative, and ask them to push for trans equality, trans protection under the law against discrimination in work and in receipt of services, adequate trans healthcare, and perhaps most importantly trans self-declaration of gender (as modelled, imperfectly, in the Republic of Ireland). Send an email to tdor.giveaway@gmail.com noting who you got in touch with and what you asked of them.

Alternatively, you can donate. Donate to one of the long list of trans organisations who do important, vital advocacy and support work for trans people, in various places around the world. If you donate, again, please send an email to tdor.giveaway@gmail.com saying to which group you donated. This post ends with some suggestions for charities to donate to.

You can enter as many times as you like, although you can only win once, and each entry must be different: that is, contacting a different rep or donating to a different charity. All entries must be received by 23:59:59GMT on December 18th. The winners will be chosen by a random draw from the entries, redrawing duplicate winners.

Feel free to comment with your own suggestions of trans charities or fundraisers for trans individuals, or with helpful scripts or form letters to send to officials, please!

List of suggested charities

- Action for Trans Health; donation link here.

- Global Action for Trans Equality (GATE), donation link here.

- Mermaids, donation link here.

- Sahodari Foundation, an Indian organisation; email to donate.

- Scottish Trans Alliance, part of the Equality Network; donation link here.

- Sylvia Rivera Law Project; donation link here.

- Transgender Law Center, donation link here.

- Trans Lifeline; donation link here.

- Trans Media Watch; donation link here.

- Trans Survivors Switchboard; donation link here, please specify the Trans Survivors Switchboard when donating.

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), donation link here.

The City of Woven Streets by Emmi Itäranta

In the City of Woven Streets, human life has little value. You practice a craft to stay alive, or you are cast out. Eliana, a young weaver in the House of Webs, knows she doesn’t belong there. She is hiding a shameful birth defect that would, if anyone knew about it, land her in the House of the Tainted.

When a mysterious woman with her tongue cut off and Eliana’s name tattooed on her skin arrives at the House of Webs, Eliana discovers an invisible network of power behind the city’s facade. All the while, the sea is clawing the shores and the streets are slowly drowning.

~~~~~

City of Woven Streets, known in the US and Canada as The Weaver and in Emmi Itäranta’s native Finland as Kudottujen kujien kaupunki, was released in June 2016 in the UK, and has been waiting in my TBR for me to get to it ever since… finally, that time has come!

The City of Woven Streets is fairly obviously a young adult novel, in terms of plot. Not only does Itäranta approach the standard rebellion against a restrictive society combined with forbidden romance angle, but she also integrates into this a kind of personal bildungsroman for Eliana in discovering her true power and role in things. It is a reasonably well executed example of its type; Itäranta’s version of an oppressive society built on a history of oppression and violence feels realistic in this regard, and the way it responds to opposition, and how the channels of power work, feel very plausible. It simply breaks no new ground, and there are certain moments, especially around the romance between Eliana and Valeria, which don’t feel like The City of Woven Streets really earned them.

The characters of The City of Woven Streets don’t stand out particularly strongly either; Itäranta’s characterisation isn’t bad per se, it’s just got a singularly unoriginal feel to it. Eliana feels like any other young adult protagonist discovering their powers and importance to the world while resisting the oppressive social order; Valeria’s muteness is virtually her only characteristic, which makes the romance between them a little strained; Weaver is the standard enigmatic, not entirely trustworthy mentor who is part of the structure of power; Alva is the wary ally; et cetera. The City of Woven Streets has characters, but none of them feel particularly real; the closest is Eliana, who at times does exhibit emotion and growth, but even her depths don’t feel very real.

The world of The City of Woven Streets is, on its face, a very creative and interesting one. Itäranta’s worldbuilding is complex and layered; the society she creates, with its rigid castes and classes, its professionalising of certain crafts as specialised to the point of not just guilds but almost monastic specialism, and its hidden, dictatorial political leadership, is one rarely seen in fantasy. The way Itäranta integrates these elements into a single society is at times very ill-considered; for instance, the gendering of certain roles like weaving and writing is stereotypical, and given the seclusion people with these roles are required to live in, the idea that they will also eventually get married seems rather strange.

This is also a world with very unclear attitudes towards queerness. At the same time, The City of Woven Streets has a couple of early references to homosexuality as a forbidden thing, but also not an uncommon thing in the cloistered single-sex environments; this would make sense were everyone’s reactions to the lesbian relationship that forms the key romance of the novel less straightforwardly accepting. The way Itäranta reveals both an intersex character and the treatment of intersex people by the society simultaneously is also rather problematic, almost brushing by the consequences of the worldbuilding she has done without really considering their implications.

Despite all this, I actually found myself enjoying The City of Woven Streets. Itäranta’s writing is fast and simple, without being simplistic; it keeps the story moving at a good lick, and draws the reader through, with hints at the broader picture and bigger world dropped from the start such that things build up slowly without too much by way of infodumping. The City of Woven Streets is almost like a packet of sweets: not as much content as one might have hoped for, and somehow disappointing afterwards, but at the time, definitely enjoyable.

If you would like to support these reviews, and the trans community, and have a chance at winning a book, all at once, please take a look at this post requesting donations or activism to trans causes.

Spice & Wolf Vol. 1 by Isuna Hasekura, trans. Paul Starr

The life of a traveling merchant is a lonely one, a fact with which Kraft Lawrence is well acquainted. Wandering from town to town with just his horse, cart, and whatever wares have come his way, the peddler has pretty well settled into his routine-that is, until the night Lawrence finds a wolf goddess asleep in his cart. Taking the form of a fetching girl with wolf ears and a tail, Holo has wearied of tending to harvests in the countryside and strikes up a bargain with the merchant to lend him the cunning of ‘Holo the Wisewolf’ to increase his profits in exchange for taking her along on his travels. What kind of businessman could turn down such an offer? Lawrence soon learns, though, that having an ancient goddess as a traveling companion can be a bit of a mixed blessing. Will this wolf girl turn out to be too wild to tame?

~~~~~

As with Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime, this was one of Jeannette Ng’s light novel recommendations; a high mediaeval fantasy about economics? Right up my street, surely?

Spice & Wolf Vol. 1 starts off promisingly enough, with the tribulations of Kraft Lawrence, a travelling merchant, without fixed abode, longing for the possibility of belonging somewhere. We meet him plying his tricks to get information, and see the way that knowledge is power, before we ever really get into the meat of the story; Lawrence is our viewpoint character, and Hasekura introduces him to us early, in all his flawed and stereotypical, simplistic ‘glory’. Holo is similarly unsubtle a character; Spice & Wolf treats her at times as a completely naive person with no knowledge of society, despite clear interactions with it, and at others as deeply knowledgeable about modern (that is, mediaeval) systems of economics.

This uneven characterisation for both is frustrating, and not helped by the constant undercurrent of romantic tension that Hasekura tries to create; Spice & Wolf wants to make Holo and Lawrence seem an obvious couple, but despite the text itself repeatedly suggesting mutual feelings, there doesn’t seem to be any real chemistry between them, only a kind of dull, muted thing that could at a glance be seen as such. Hasekura’s writing of people all tends towards that, in this volume; no one really has a personality, they are pieces on the board to be moved around to fit the plot.

The setting does little to allay this problem. Spice & Wolf is set in a stereotypical high-mediaeval pseudo-Mitteleuropa, dominated by a monotheistic Church intent on stamping out paganism and killing demons and the possessed. It’s a collection of microstates and trading companies and free cities, whose interdependence and interconnections are assumed but not clear; we seem to jump from mediaeval feudalism in one moment to a guild structure in the next, from kingdoms and dukedoms to city-states. Hasekura’s care and attention to aspects of the worldbuilding is patchy, at best; indeed, it often feels like the world of Spice & Wolf exists to allow Hasekura to explain economic principles, rather than for those economic principles to actually make sense.

The plot of Spice & Wolf is a quiet, small thing, at first; what starts as a minor deal to get in on the ground in a bit of currency speculation quickly spirals out of control into a matter of rival merchant consortia kidnapping and counter-kidnapping. Hasekura is assured in his action sequences, with fast-paced movement and some really heart-pounding moments, but these are few and far between. What advances the plot far more are economic discussions or negotiations between merchants. While Hasekura makes some of these negotiations fascinating through showing as much what’s going on behind the spoken words as what’s actually said, on the whole, they can drag a bit. This is especially true when Spice & Wolf devolves into Lawrence simply explaining to Holo exactly what currency speculation is, or how a commodity currency works, or what devaluation of a currency means; they feel rather stilted and intrusive on the plot.

In the end, Spice & Wolf Vol. 1 is an interesting attempt at writing an economics-based epic fantasy, but Hasekura can’t quite make it work.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime by Mizuku Nomura, trans. Karen McGillicuddy

High school student Konoha Inoue is a gifted writer who’s lost his passion for his craft. When he meets beautiful upperclassman Tohko Amano, though, he finds someone with a greater hunger for literature than anyone he’s ever met… literally!

Amano is a book-scarfing goblin who satisfies her cravings by munching on the printed works of history’s greatest authors. However, nothing is as delicious as the handwritten stories she bullies Konoha into writing for her.

When a desperate classmate approaches the “literature club” to draft love letters on her behalf, the very thought of it sets Tohko’s mouth watering! But as Konoha will discover, the greatest love stories are often the most tragic…

~~~~~

Jeannette Ng, of last week’s Under the Pendulum Sun review, some little while ago had a thread of light novel recommendations. I’ve been curious about light novels for a while now, and so took these up…

Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime is an odd little book, which starts off as one thing before slowly morphing into quite a different book. It seems, at first glance, to be quite a frothy little novel, a story about high school romance, subterfuge, and misplaced or unrequited love; Nomura leans heavily into the frilly side of the novel as she kicks proceedings off. It is only as the book continues and developes that a darker theme emerges; Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime isn’t about a love story, it’s an investigation into a death, an investigation Konoha and Tohko have been tricked into by seemingly-chirpy Chia Takeda, a first year.

The slide from one plotline into the other is strangely smooth; Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime builds up the romantic plotline as a standard schoolgirl romance, unrequited and of an older student, before Konoha’s attempts to learn more about this older student turn up the fact that he doesn’t actually exist. Nomura doesn’t lean heavily on supernatural elements, although Konoha assumes they are in play; instead, this is essentially, but for the book-eating girl herself, a dark piece of mimetic fiction, and the plot reflects that, with its plotting that has more than a hint of the Shakespearean to its resolution.

Shakespeare is not the only literary touchstone for Nomura in Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime. Not only does Tohko reference the different way different authors taste repeatedly, and show an incredible engagement in literary criticism and a deep engagement with various texts, but the whole book is built in conversation with Osamu Dazai. Indeed, many of the decisions characters make are heavily influenced by, and structured around, Dazai’s final work, No Longer Human; all the characters have read it, and there is explicit engagement with it in the context of Dazai’s wider ouevre, making literary criticism a key plot point for this novel.

Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime is also a fascinating book for its characterisation; everyone has a full and interesting personality, and the degree to which things like depression and angst are treated sympathetically is incredibly powerful. Indeed, Nomura’s discussion of different presentations of difference and depression, and the coping and deflection methods teenagers may develop to mask it, is moving in its accuracy; characters aren’t flattened by their mental health difficulties, only altered by them, and we have to see people in new lights as we learn more about them. This is a rare nuanced approach, and the way it manifests in the central cast is really well written.

The problem comes in the way Nomura treats the physicality of the female characters; Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime seems almost to become a different novel temporarily at times, as the bodies of the girls in the cast are discussed in pornographic, prurient, male-gaze ways that really intrude on the way the rest of the book is written. By turns deeply thoughtful and whimsically light, Nomura’s occasional succumbing to the pressures of certain conventions of how one describes a girl’s body really jar when they appear.

In the end, Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime isn’t high art, but it is deeply thought and felt art; it’s breezy, and eases you into its darkness, but Nomura really does carry that darkness well. A fascinating read.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.

Mapping the Interior by Stephen Graham Jones

Walking through his own house at night, a fifteen-year-old thinks he sees another person stepping through a doorway. Instead of the people who could be there, his mother or his brother, the figure reminds him of his long-gone father, who died mysteriously before his family left the reservation. When he follows it he discovers his house is bigger and deeper than he knew.

The house is the kind of wrong place where you can lose yourself and find things you’d rather not have. Over the course of a few nights, the boy tries to map out his house in an effort that puts his little brother in the worst danger, and puts him in the position to save them . . . at terrible cost.

~~~~~

It’s after Halloween, but still time for one last good chilling read…

Stephen Graham Jones’ Mapping the Interior is an odd little novella, about culture, about family, about love, and about the lengths one will go to for those we care about. Jones’ story is about a family of Native Americans who left the reservation after the death of the father of the household, moving to a poverty-stricken exurb; their physical environment is as much a source of horror as the supernatural elements that appear in the story.

Jones brings this environment into the stark foreground incredibly powerfully; Mapping the Interior is as much concerned with mapping the prefab house the family lives in, in all its different parts, as anything more interior to the family, and indeed, the unfolding mapping of the house plays a major role in the unfolding strangeness and horror of the plot. Jones describes the house in detail, through the eyes of a child; it’s a very effective approach, as we build a complete picture up only in snapshots, and somewhat impressionistic ones, as much emotional as physical.

The main horror of Mapping the Interior is built up slowly; Jones starts the novella off looking like one kind of ghost story, and then turns around and writes a rather different, darker, more horrifying kind. The way this is achieved is through the dawning realisation of a child of the reality of his dead father’s return; at first, he thinks of it as a blessing, his father come back to him, but the cost of this return becomes increasingly clear as the novella goes on, even as the benefits are shown. It’s a dark story, and Jones doesn’t shy away from its darkest elements; the gut physicality of violence is painfully clear, as is the familiarity with it of our twelve year old protagonist and narrator, Junior.

There are also banal horrors around; Jones doesn’t overlook the effects of racism, or of ableism directed at a developmentally delayed child, Dino, on a Native American family. Indeed, one of the biggest horrors of Mapping the Interior comes from a violent pack of dogs kept by one of the neighbours, who seem more like coyotes than domestic canines; their desire to eat the children of the family is powerful and brutal, and Jones really brings the fear of them home, with a visceral reality. These horrors are the backdrop to the supernatural horrors, and indeed almost an alternative to them; they make the supernatural seem more benevolent at the start, before its true nature becomes clear.

This isn’t a perfect novella; Mapping the Interior has a tendency to treat developmental delay as a comic relief motif or as the effect of supernatural agency, although Jones is fundamentally writing about Dino with sympathy. Some of the key plot points turn on his unspecified condition, and the way it is treated is at times deeply frustrating. Furthermore, Jones’ tendency to cut away at key moments, for various somewhat contrived reasons, cuts the tension a bit, and makes the novella more convoluted than it has to be.

In the end, though, despite these problems, Mapping the Interior is a powerful, dark, and moving novella, with a real chill at its heart.

If you found this review useful, please support my ability to write by contributing to my Patreon.